Document 11283888

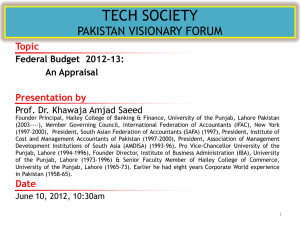

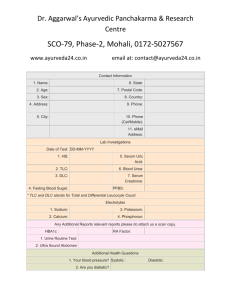

advertisement