Document 11283888

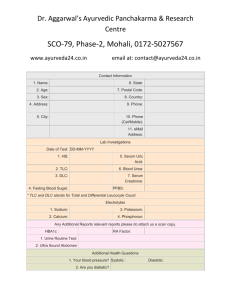

advertisement