Understanding the Dynamics of Drug-Related Problems in... and its Surrounding Neighborhood

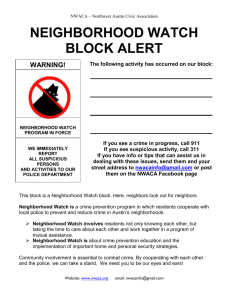

advertisement