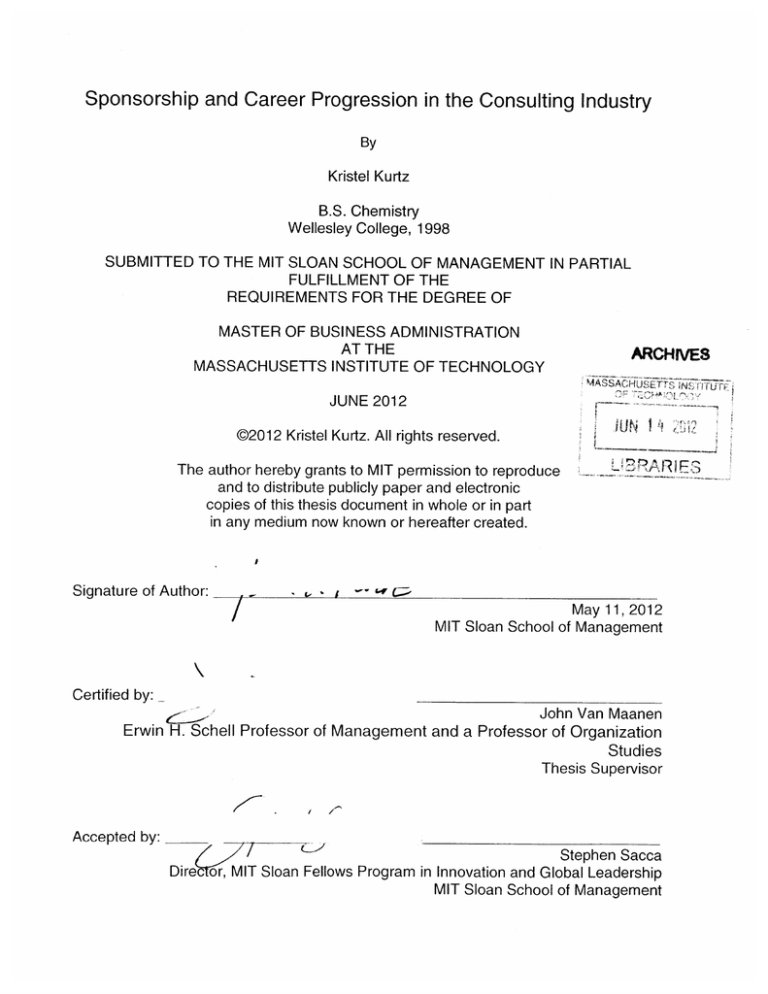

Sponsorship and Career Progression in the ... ARCHIVES

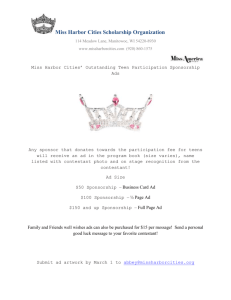

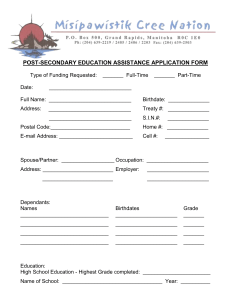

advertisement