Integration and operation of post-combustion capture system ... generation: load following and peak power

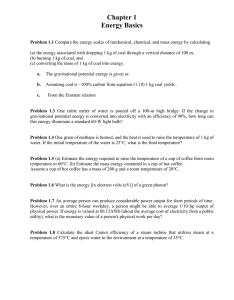

advertisement