GOING TO WAR WITH THE ALLIES YOU HAVE: ALLIES, COUNTERINSURGENCY, Daniel Byman

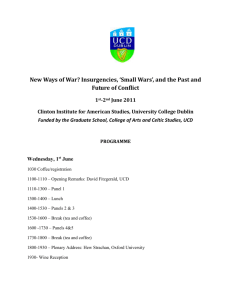

advertisement