Memorandum on the Application of International Standards of Due Process by the

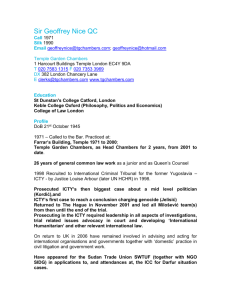

advertisement