AN by (1969) SUBMITTED IN

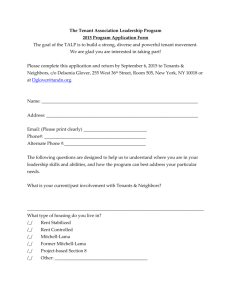

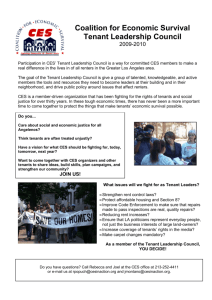

advertisement