Resource Recovery in Belmont Massachusetts , Brunswick, Maine

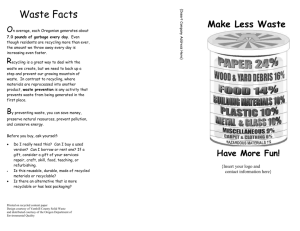

advertisement