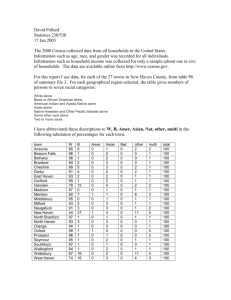

Knowing No Boundaries: Stemming the Tide ... Several Southern Connecticut Towns and the Lessons ...

advertisement