Comprehensive Permitting: By Jeffrey B. Litwak

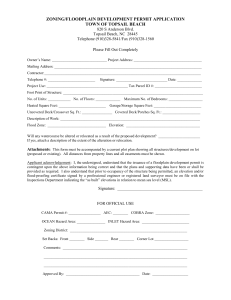

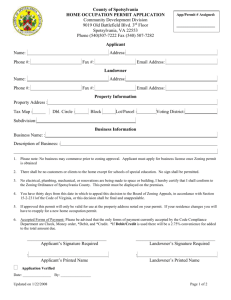

advertisement