THE CONVERSION OF GARAGES FOR RESIDENTIAL PURPOSES

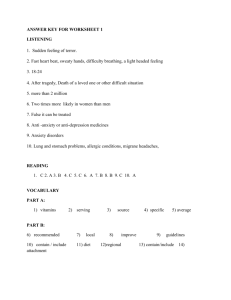

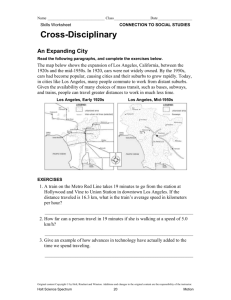

advertisement