Theoretical and Empirical Observations

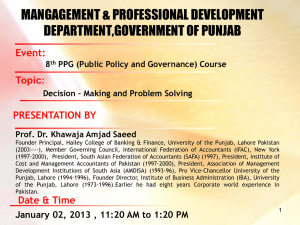

advertisement