Document 11277990

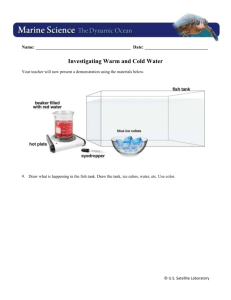

advertisement