I H Q Y

advertisement

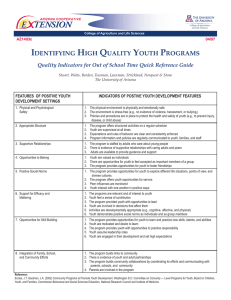

ARIZONA COOP E R AT I V E E TENSION College of Agriculture and Life Sciences AZ1403f 04/07 IDENTIFYING HIGH QUALITY YOUTH PROGRAMS Information for Middle School Youth Professionals Tessman, Stuart, Lauxman, Waits, Borden, Strickland, Norquest & Stone The University of Arizona Overview The purpose of this fact sheet is to inform Youth Development Professionals on research findings regarding important features of successful youth programs. The goal is to offer individuals who work with youth in grades 6-8 guidelines for identifying high quality programs. Topic/Text Studies repeatedly find that participating in well-run, quality youth programs is beneficial for young people (Redd, Cochran, Hair, & Moore, 2002; Villarruel, Perkins, Borden, & Keith, 2003). The National Research Council (Eccles & Gootman, 2002) provides a framework describing eight features of positive youth development settings. The following is a summary of research recommendations and findings for youth professionals to consider when planning, designing, and evaluating a quality youth program for middle school youth. Physical and Psychological Safety Youth participate in diverse out-of-school programs to have fun with friends and learn new skills. These activities may be diverse and include sports, creative arts, and community service (Lauver, Little, & Weiss, 2004). For youth to benefit from their participation, these activities should take place in a location that is safe and inviting. To improve the quality of time spent in out-of-school activities, program settings should ensure that youth are safe from threat of violence, harassment or harm (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). Appropriate Structure Youth feel secure when there are clear rules and guidelines for behavior. While middle school youth need to explore their identity to figure out who they are, they still need supervision and limits. Adolescents with less supervision are more likely to participate in dangerous behavior due to peer pressure (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Many youth prefer to join structured activities when they are available (Hall, Israel, and Shortt, 2004). Supportive Relationships Youth believe they are a part of a high quality program when adults consistently demonstrate their concern and support for them (Duffett, Johnson, Farkas, Kung, & Ott, 2004). Youth benefit from positive role models outside of their family (Miller, 2003). Successful youth programs are staffed by adults who are creative, well trained, and are able to build long-term relationships with youth participants (Hall, et al., 2004). Opportunities to Belong When youth experience a sense of belonging, they behave more responsibly. They feel more confident and have a better attitude toward school (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). It is important that youth feel that they are valued both as an individual and as part of a group. Quality programs provide youth with activities that offer a chance for recognition by friends, family, and community. Positive Social Norms In high quality programs, caring adults work with youth to set positive guidelines for behavior. Youth who join a team or club experience more positive outcomes than those who have a lot of time to themselves after school (Duffett, et al., 2004). Young people benefit from the chance to explore different life situations, viewpoints, and cultures. It is especially helpful to be around other youth who have positive goals (Miller, 2003). Research connects boredom and problem behavior (Duffett et al., 2004). Thus, participation in youth programs reduces juvenile crime and violence by offering youth a positive alternative for out-of-school hours (Hall, et al., 2004). Support for Efficacy and Mattering In high quality youth programs, young people are encouraged to better themselves and their communities (Miller, 2003). In such programs, youth and adults share 8 Features of Positive Youth Development Settings • • • • • • • • Physical and Psychological Safety Appropriate Structure Supportive Relationships Opportunities to Belong Positive Social Norms Support for Efficacy and Mattering Opportunities for Skill Building Integration of Family, School, and Community Efforts leadership, with young people given the chance to lead when they are ready. Youth input should matter and help to drive the program’s goals and activities. Quality youth programs provide youth an opportunity to be included in decision-making (Hall, et al., 2004). Quality youth programs recognize the diversity of youth participants and accommodate the interests and values of youth from different cultures. Youth want to learn important skills and to know that their time is worthwhile. Program activities can be academic, artistic, or community service-based. Opportunities for Skill Building Youth programs provide opportunities to develop life skills such as teamwork, problem solving, and communication (Miller, 2003). Successful programs provide challenging and age appropriate activities. Younger adolescents begin with pre-apprenticeships that combine hands-on and academic enrichment activities. Later, they transition to supervised internships that focus on learning skills and producing a product (Hall, et al., 2004). Integration of Family, School, and Community Efforts Young people stay involved when connected with peers, family, school, and community. For example, studies show that: • Youth do better in school when parents are involved (Rhodes, Grossman, & Resch, 2000). • When parents are involved in a program, youth are more likely to be involved themselves (Weiss & Brigham, 2003). • Community-based programs that are connected to the schools increase student learning and success (Epstein, 2001). Quality youth programs facilitate positive youth outcomes by integrating the settings of daily life. This integration improves the overall level of support youth receive. References Duffett, A., Johnson, J., Farkas, S., Kung, S., & Ott, A. (2004). All work and no play? Listening to what kids really want from out-of-school time. Retrieved from the Public Agenda Web site3/30/06 http://www.publicagenda.org/research/research-/ reports Eccles, J., & Gootman, J. A. (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, DC: Committee on Community-Level Programs for Youth. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences Education, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Epstein, J. L. (2001). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Hall, G., Israel, L., & Shortt, J. (2004). It’s about time! A look at out of school time for urban teens. Wellesley, MA: The National Institute on Out-of-School Time. Lauver, S., Little, P., & Weiss. (2004, July). Moving beyond the barriers: Attracting and sustaining youth participation in Out-of-School Time Programs (No. 6). Cambride, MA: Harvard Family Research Project. Miller, B. M. (2003). Afterschool programs and educational success. Critical hours: Executive summary. Quincy, MA: Nellie Mae Education Foundation. Redd, Z., Cochran, S., Hair, E., & Moore, K. (2002). Academic achievement programs and youth development: A synthesis. Washington, DC: Child Trends Rhodes, J. E., Grossman, J., & Resch, N. (2000). Agents of change: Pathways through which mentoring relationships influence adolescents’ academic adjustment. Child Development, 71, 1662-1671. Roth, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). What Do Adolescents Need for Healthy Development? Implications for Youth Policy. Social Policy Report, 14, 1. Villarruel, F. A., Perkins, D. F., Borden, L. M., & Keith, J. G. (2003). Community youth development: Practice, Policy, and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Weiss, A. R., & Brigham, R. A. (2003). The family participation in after-school study. Boston, MA: Institute for Responsive Education. Available at www.responsiveeducation.org/ current.html#After-school THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES TUCSON, ARIZONA 85721 DARCY TESSMAN Associate Extension Agent MARTA ELVA STUART Associate Extension Agent LISA LAUXMAN Extension Acting Assistant Director JUANITA O’CAMPO WAITS Extension Area Agent LYNNE BORDEN Extension Specialist, Associate Professor BRENT STRICKLAND Associate Extension Agent JAN NORQUEST Area Associate Extension Agent MARGARET STONE Research Associate This information has been reviewed by university faculty. cals.arizona.edu/pubs/family/az1403f.pdf Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, James A. Christenson, Director, Cooperative Extension, College of Agriculture & Life Sciences, The University of Arizona. The University of Arizona is an equal opportunity, affirmative action institution. The University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, veteran status, or sexual orientation in its programs and activities. 2 The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension