Examining Gender Bias in Studies of Innovation

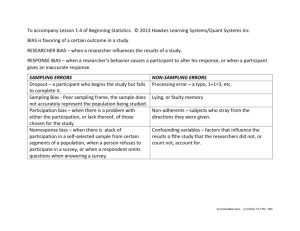

advertisement