GAO BANK SECRECY ACT

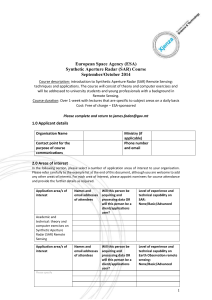

advertisement