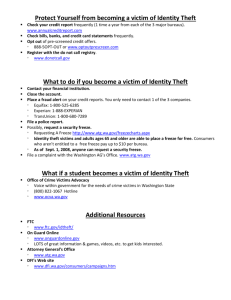

a GAO IDENTITY THEFT Some Outreach

advertisement