GAO CYBERSECURITY National Strategy, Roles, and

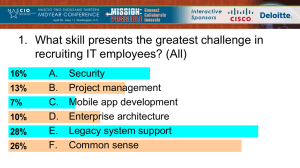

advertisement