GAO AVIAN INFLUENZA USDA Has Taken Important Steps to

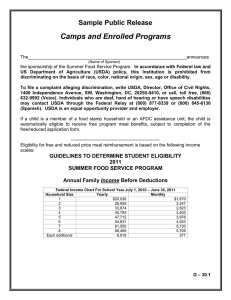

advertisement