GAO INFLUENZA PANDEMIC Sustaining Focus on

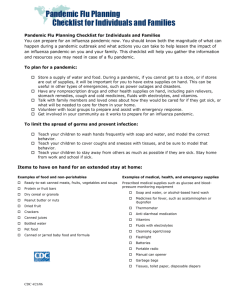

advertisement