GAO HOMELAND SECURITY Transformation

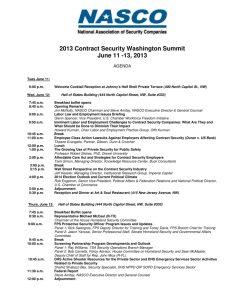

advertisement