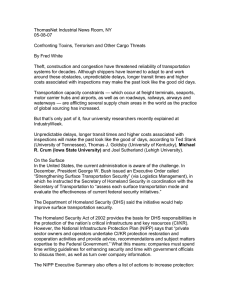

GAO TRANSPORTATION SECURITY

advertisement