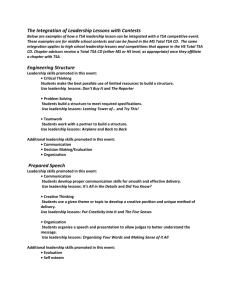

GAO COMMERCIAL VEHICLE SECURITY Risk-Based Approach

advertisement