GAO PUBLIC HEALTH AND BORDER SECURITY

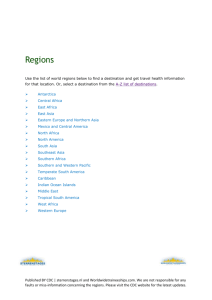

advertisement