GAO HOMELAND DEFENSE Continued Actions

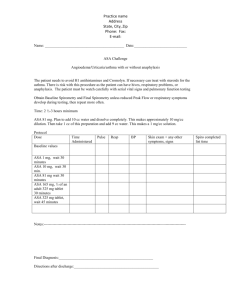

advertisement