GAO TSA EXPLOSIVES DETECTION CANINE PROGRAM

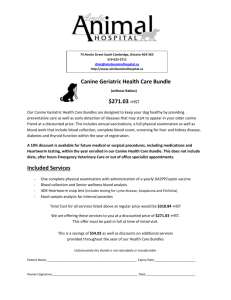

advertisement