Document 11272794

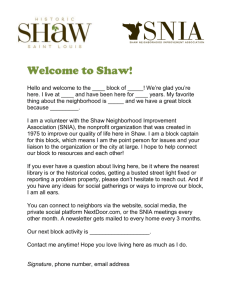

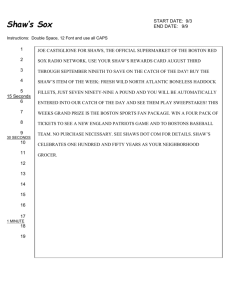

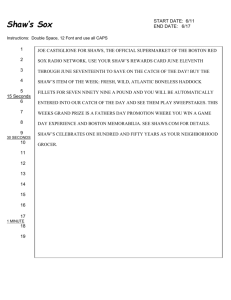

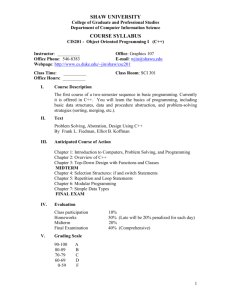

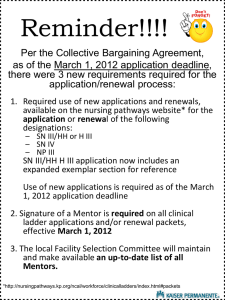

advertisement