Signature redacted ARCHVES LIBRARIES

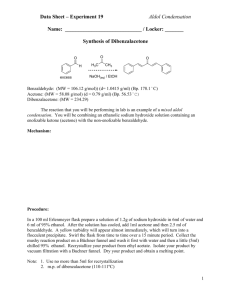

advertisement