Document 11269327

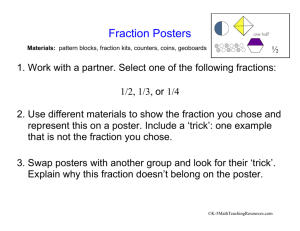

advertisement