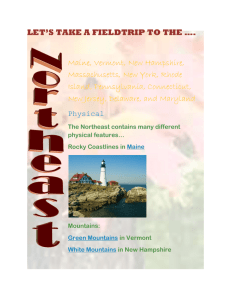

Locally Grown: Statewide Land Use Planning ... Northern New England

advertisement