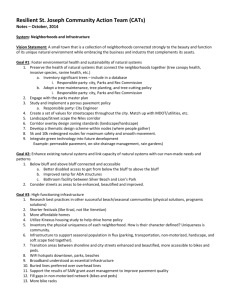

ROTCHj4 Valuing Open Space:

advertisement