City Connects in Catholic Schools Evaluation Summary Report 2014

City Connects in Catholic Schools

Evaluation Summary Report 2014

Boston College Center for Optimized Student Support

Acknowledgements

City Connects in Catholic Schools would like to thank our partners who support our work in Boston-area Catholic elementary schools. Their ongoing support is vital to our work.

The Catholic Schools Foundation has made a sustained commitment to implementing and expanding City Connects in Catholic Schools.

The Mathile Family Foundation has enabled City Connects to adapt its model to high schools and has supported the expansion of City Connects in

Catholic elementary schools in Ohio.

The Better Way Foundation has provided support for the Early Childhood

Adaptation of City Connects in Catholic Schools and for its expansion to all

City Connects schools.

The Archdiocese of Boston’s Catholic Schools Office has been a supportive partner in the implementation and evaluation of City Connects in Catholic

Schools.

Our community agency partners across the cities of Boston and Chelsea have established and sustained partnerships with City Connects School

Site Coordinators, the schools, students, and families.

Boston College and the Lynch School of Education have a deep and longstanding commitment to address the non-academic barriers to learning.

The principals, teachers, and City Connects School Site Coordinators have inspired us with their deep and daily commitment to children, communities, and Catholic education.

The ongoing work of implementing and evaluating City Connects in

Catholic Schools is not possible without the generosity and resolve of all of our partners. It is our shared commitment to children and communities that makes this work possible and successful.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014 i

Introduction

Underlying discouraging reports of increasing economic disparity and rising rates of child poverty in the United States 1 is the long-recognized— but often ignored—fact that children growing up poor face exceptional challenges outside of school that impede success in school. Current research confirms that larger social structures and contexts beyond the school are critical, accounting for up to two-thirds of the variance in student achievement.

2 Urban Catholic elementary schools face the same challenges as their public school counterparts: they serve neighborhoods that show high concentrations of poverty and students who struggle with the impact of poverty on academic achievement.

3 It is now widely recognized that urban schools cannot close the achievement gap without a systemic approach to addressing out-of-school factors.

4 While the challenge of poverty may be society’s to solve, and not all non-academic barriers to learning can or should be addressed by schools, in the absence of a largescale societal solution, schools are in a position to provide some supports that mitigate the impact of poverty.

Over the course of 12 years, staff at the Lynch School of Education at

Boston College have developed and implemented a theoretically-guided, evidence-based approach to student support in high-poverty urban schools.

This approach, called City Connects, is novel in that it: a) is systematic, using a student support professional in each school to transform and optimize existing school structures and processes in order to make student support practices a codified and core aspect of schools that permeates all functions of schools as institutions; and b) is tailored, identifying each student’s strengths and needs in academic, social-emotional, physical, and family domains and leveraging community-based services to deliver support that is aligned with these strengths and needs. This approach redefines the traditional and often haphazard approach to student support in most schools.

Under the leadership of Boston College, City Connects was formally adopted by Boston Catholic elementary schools (K-8) in 2008-09.

Historically, Catholic elementary schools have made important contributions to closing the achievement gap between low-income students and those from higher-income families. The Catholic value of caring for

“the whole person” makes Catholic schools a natural fit to address the

1 Bertlsmann Foundation, 2011; Blow, 2011; Kahn & Martin, 2011; Tavernise, 2012

2 Rothstein, 2010; Phillips, Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Crane, 1998

3 Cattaro, 2002; Fenzel & Domingues, 2009; O’Keefe & Scheopner, 2009

4 Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

1

adverse impact of poverty on academic growth. City Connects and Boston’s

Catholic schools are capitalizing on their shared values not only to close the achievement gap, but also to support students in the Catholic tradition of caring for the entire human person.

More than 10 years of research and evaluation in Boston Public Schools has shown that City Connects has significant, positive outcomes in student achievement and thriving (behavior, work habits, and effort). Further, after students leave the intervention in Grade 5, it has a significant, longterm, beneficial impact on academic achievement, chronic absenteeism, and school dropout.

This report summarizes the most recent findings of the evaluation of City

Connects in Catholic Schools. Wherever possible, results are reported for the 2012-13 school year, when the City Connects model was implemented in 16 urban Catholic elementary schools in the Archdiocese of Boston.

5

In some places in this report, results from the 2011-12 school year are the most recent available. This report includes sections summarizing the program’s impact on students, as well as on school-based professionals and organizations partnering with the program. Central to the evaluation of

City Connects in Catholic Schools is the Early Childhood Adaptation of the

City Connects model; outcomes for early childhood are also presented.

5 A separate document reports on implementation and evaluation in Dayton, OH Catholic schools.

2 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

The City Connects Intervention

Rationale and Partner Schools

For children living in poverty, the impact of out-of-school factors is clearly evident in their ability to succeed in school. Limited resources, stress, and the chaos of poverty result in poor attendance, high mobility, socialemotional dysfunction, a lack of readiness for school, and limited cultural capital to understand schools as institutions.

6 Rothstein describes the impact on achievement of out-of-school factors relative to in-school factors:

Decades of social science research have demonstrated that differences in the quality of schools can explain about one-third of the variation in student achievement. But the other two-thirds is attributable to non-school factors (emphasis added).

7

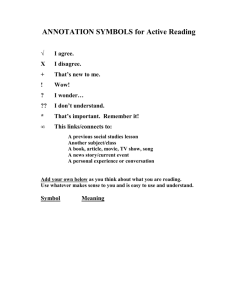

Figure 1 illustrates that academic success is predicated on children’s readiness to engage and thrive in school. It also shows the overlapping impact of the various domains of development on children’s readiness to learn and thrive.

Figure 1. Academic Success is Predicated on Students’ Readiness to Engage and Thrive in School

Many schools currently are unable to respond to the pressing challenges facing students’ out-of-school lives. Student support structures are the product of an earlier time, a different set of needs, and a less diverse demographic. The typical approach to student support in most schools:

6 Dearing, 2008

7 Rothstein, 2010

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

3

1. Is fragmented and idiosyncratic, serving a small number of highneed students

2. Does not address the full range of needs, focusing mainly on risk

3. Does not collect data on the effectiveness of the supports offered students

4. In practice, does not operate as a core function of the school, and as a result, seeks minimal teacher engagement 8

In contrast to these earlier approaches, optimized student support has six identifying characteristics. It is:

1. to the unique strengths, needs, and interests of each student

2. , serving the academic, social/emotional, health, and family needs of all students from a variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds

3. among families, schools, and community agencies

4. to schools by leveraging the resources provided by community agencies

5. for effectiveness through collecting and analyzing data to evaluate and improve service delivery and student outcomes

6. Implemented in all sites with fidelity and oversight

Grounded in these best practices, City Connects in Catholic Schools is a partnership between Boston College, community agencies, and Catholic elementary schools in the Archdiocese of Boston. The partnership delivers optimized student support in participating schools, which are located in several Boston neighborhoods, including East Boston, the

North End, Dorchester, Roxbury, the South End, Roslindale, South

Boston, and West Roxbury, and in two communities outside of Boston

(Chelsea and Brookline). In 2012-13, City Connects was implemented in 16

Catholic schools; total student enrollment in grades Pre-K through grade

8 during 2012-13 was 4,428. Table 1 presents demographic information on participating schools for 2012-13.

8 Walsh & DePaul, 2008

4 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Table 1. City Connects Catholic School and Comparison Elementary School Characteristics,

2012-13

City Connects Schools

(N=16)

Comparison Schools

(N=9)

Gender

Male

Race

Asian

Black

Hispanic/Latino

White

Multi/Other

Free/Reduced Price Lunch

Registering as Eligible

49%

8%

21%

19%

34%

17%

27%

47%

13%

14%

10%

54%

9%

22%

Total Students 4,362 2,707

*Total number of students is slightly lower than the total reported above because demographic records were incomplete for a small set of students.

Data compiled from City Connects in Catholic Schools records collected from individual schools and Archdiocese of

Boston Catholic Schools Office records.

Description of the City Connects Intervention

The mission of City Connects is to have children engage and learn in school by connecting each child with the tailored set of prevention, intervention, and enrichment services he or she needs to thrive. There are six key components of the model:

School Site Coordinator.

At the core of the intervention is a full-time

School Site Coordinator (SSC) in each school, trained as a school counselor or school social worker, who connects students to a customized set of services through collaboration with families, teachers, school staff, and community agencies. The SSC follows standardized practices codified in the City Connects Practice Manual, which are schematized in Figure 2 and described in detail below.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

5

Figure 2. City Connects’ Student Support Process

Whole Class Review.

The SSC works with each classroom teacher to review every student in the class and develop customized support plans that addresses their individual strengths and needs. There are five aspects of the Whole Class Review (WCR):

1. Identifying the strengths and needs of each student across four domains (academic, social/emotional/behavioral, health, and family)

2. Identifying and locating appropriate school- and/or communitybased services and enrichments

3. Establishing the connection between these service providers and individual children and their families

4. Documenting and tracking the delivery of the service

5. Following up to ensure appropriateness of fit

As they conduct the WCR, at the most general level, the teacher and SSC group the students in a class into three tiers: strengths and minimal risk

(Tier 1); strengths and mild to moderate risk (Tier 2); or strengths and severe risk (Tier 3). Tier 2 is divided into two levels: 2a (mild risk) and

2b (moderate risk). Figure 3 shows the percentage of students in Early

Childhood and later elementary grades classified at each level.

6 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Figure 3. Percentage of Students at Each Level of Risk, Early Childhood and Elementary Grades

Data source: SSIS, 2012-13

Individual Student Review.

Students identified as having intensive needs, at any point during the school year, receive an Individual Student

Review (ISR). A wider team of professionals discuss and develop specific measureable goals and strategies for the student. The ISR is conducted by the student support team—an existing school structure that can include school psychologists, teachers, principals, nurses, and occasional community agency staff members and that is typically led by the SSC. The

SSC communicates with the family before and after the ISR. In 2012-13, 5% of students received an ISR.

Community agency partnerships.

A critical aspect of the role of the SSC is developing and maintaining partnerships with community agencies and institutions. These relationships are vital to providing all students with the supports and enrichments they need to thrive. In 2012-13, services were delivered by 190 different community partners.

Connecting students to services, tracking, and following up.

During and after the conversations with teachers, school staff and leaders, and community agency representatives, City Connects SSCs connect each student to the particular enrichment and service programs that best meet his or her strengths and needs. SSCs work closely with families as students are referred and connected to particular enrichments and services.

To aid with the process, and to permit streamlined tracking and followup, City Connects has developed a proprietary Web-based database, the Student Support Information System (SSIS). SSIS allows for secure collection of data on student reviews, individual student plans, service

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

7

referrals, and providers (both school-based and community agencies) who deliver services. SSIS data are used for three purposes:

1) record-keeping at the individual and school level; 2) monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the intervention throughout the school year; and 3) conducting research on the effectiveness of the intervention.

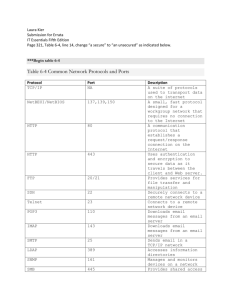

Services can be classified into three broad categories: prevention and enrichment; early intervention, and intensive/crisis intervention. Each category includes services of different types. The tailoring of services is accomplished through different combinations of quantity and type of services from Table 2, resulting in a unique set of services for each student.

Table 2. Total Number of Service Referrals, by Category

Number of

Services

Category 1

(Prevention and

Enrichment)

After-School Program

Enrichment: Youth Development

Enrichment: Arts

Sports or Physical Activity

Health Screening – Vision

Health Screening – Hearing

Enrichment: Academic

Health Screening – BMI

Before-School Program

Health Screening – Postural/ Scoliosis

Summer Programming: Enrichment

Violence Prevention

School Vacation Program

Summer Programming: Academic

Category Total

1,996

619

549

224

210

1,818

1,347

1,324

700

102

83

68

65

1

9,106

Percentage of Category

Percentage of All

Services

22%

7%

6%

2%

2%

20%

15%

15%

8%

1%

1%

1%

1%

<1%

59%

8 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Category 2 (Early

Intervention)

Category 3

(Intensive/Crisis

Intervention)

Grand Total

Academic Classroom Support

Mentoring

Psycho-Social Group

Individual Tutoring

Classroom-based Social Skills Intervention

Classroom-based Health Intervention

Math Intervention

Literacy Intervention

Behavioral/Social

Family Conference/Meeting

Behavioral Support: City Connects School

Site Coordinator

Academic Support

Supplemental Educational Services (SES)

Parent/Family Engagement

Parent/Family Support

Family Assistance

Staff Mentoring

ESL

Parent/Family Donations

Classroom/Group Health Intervention

ESL-Parent/Family

Classroom/Group Social Skills Intervention

Category Total

Health/Medical

Counseling: Student

Regular Check-in with City Connects

School Site Coordinator

Violence Intervention

Special Education Evaluation

Crisis Intervention

Informal Screening/Diagnostic

Counseling: Family

Attendance Support

Occupational Therapy

Independent Evaluation

Category Total

Data source: SSIS, 2012-13.

6%

5%

4%

3%

3%

21%

15%

9%

9%

8%

7%

<1%

<1%

52%

1%

<1%

<1%

<1%

2%

2%

2%

1%

1%

25%

10%

<1%

<1%

5%

4%

2%

1%

1%

1%

1,915

15,398

5

1

41

17

87

78

14

14

4,377

990

4

2

7

4

25

11

481

187

66

64

87

67

54

257

210

189

145

144

941

673

411

376

352

288

28%

12%

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

9

For any single student, regardless of tier, the tailored set might include a combination of prevention and enrichment, early intervention, and/or intensive services.

Table 3.

Average Number of Service Referrals by Tier

Tier

2b

3

1

2a

Total

Students Referred to Services

1708

1254

670

256

3888

Data source: SSIS, 2012-13.

*Average includes only students referred to services.

Table excludes inactive students and students not assigned to a tier.

Average Number of

Service Referrals*

2.8

3.5

4.4

5.9

3.5

As Table 3 shows, the average number of service referrals per student was highest in the tier corresponding to most severe risk (Tier 3) and lowest in the tier corresponding to minimal risk (Tier 1). Similarly, students in

Tier 1 were typically referred to less intensive services, while students in higher tiers were referred to more intensive services, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Percentage of Service Referrals in each Category, by Level of Risk

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Category 3 (Intensive/Crisis

Interven>on)

Category 2 (Early Interven>on)

Category 1 (Preven>on and

Enrichment)

Tier1 Tier 2a Tier 2b Tier 3

Data source: SSIS, 2012-13.

Figure 4 shows that as tier (representing level of risk) increases, the proportion of intensive services also increases; for example, Tier 3 students received over twice as many referrals to intensive and crisis intervention services as those in Tier 1.

10 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

City Connects in Catholic Schools

History of City Connects in Catholic Schools

On the basis of the evaluation and success of City Connects in public schools, key stakeholders pursued the implementation of a similar program for Catholic elementary schools. In 2003, City Connects staff at Boston College conducted a needs assessment of Boston Catholic elementary schools, revealing that urban Catholic school children face significant barriers to learning on a level comparable to their public school counterparts. From 2004 to 2008, Boston College offered professional development seminars (six sessions annually) to principals and school counselors on implementing various aspects of systemic student support.

While this professional development effort facilitated an introduction to the City Connects model, it was not intended to result in consistent, systemic implementation across schools.

In September 2008, the Archdiocese of Boston’s Office of Catholic Schools, the

Catholic Schools Foundation, and Boston College collaborated to fund and pilot a more formalized and systemic implementation of the City Connects model across a cluster of Catholic elementary schools in Boston. City

Connects is now in 16 Catholic elementary schools in Boston and in two highpoverty Catholic schools just outside of the city (Chelsea and Brookline).

In 2008, the Mathile Family Foundation supported the implementation of the City Connects model at Our Lady of the Rosary K-8 School in Dayton,

Ohio. Dayton is also the site of the first high school adaptation of City

Connects at Chaminade-Julienne Catholic High School. The City Connects implementation in Catholic schools in Dayton is described in detail in two separate reports.

9

In 2009, the Better Way Foundation (Minneapolis, MN) provided a 3-year grant to adapt the City Connects model to the early childhood population.

City Connects in Catholic Schools committed to develop, implement, and evaluate an Early Childhood Adaptation of the City Connects model in participating schools in Boston as well as in free-standing Early

Childhood centers sponsored by Catholic Charities.

10 Reports detailing the particulars of the Early Childhood Adaptation were prepared for the Better

Way Foundation in September 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013. These reports incorporated data from our evaluation of the Early Childhood Adaptation.

9 Hursh, DiNatale & Walsh 2010, 2011

10 For the purposes of this program, “early childhood” is a term that refers to children enrolled in grades K0 (or pre-kindergarten) through 1st grade.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

11

Professional Development

City Connects School Site Coordinators participate in biweekly professional development sessions at Boston College. Delivered by the

City Connects Program Manager, the professional development series is designed to support the implementation of the City Connects model.

Sessions include training in core elements of the model, regular reviews of data from participating schools in order to inform practice, exploration of developmental research relevant for the early childhood population, discussion of relevant case examples, and presentations on timely issues for schools (e.g., bullying, autism, and special needs).

Principals attend three quarterly professional development meetings at

Boston College. SSCs are included in these meetings in order to maximize efficient collaboration. The meetings focus on the data from the evaluation of City Connects, the implementation of the model in each principals’ school, and the overall goals and direction of City Connects.

Fidelity of Implementation

Practice data collected through SSIS shows that core elements of the

City Connects model are being implemented with fidelity in Catholic elementary schools. As noted above, to assess the strengths and needs of each student, SSCs work closely with each classroom teacher to conduct a Whole Class Review. The review is a core element of the practice, providing the information the Coordinator and teacher use to tailor an individual plan of services and enrichments for each student. In 2012-13,

100% of students received this comprehensive review.

Students identified as experiencing significant risk are referred to an

Individual Student Review (ISR). As described above, this intensive review brings a team of professionals together for a careful assessment of the student’s strengths and needs and the construction of specific goals and a plan for the student. Five percent of students received this intensive review.

Fidelity to the model was also seen in SSCs’ leadership role in Student

Support Teams, where ISRs are conducted. Most SSCs chaired or cochaired weekly or biweekly SST meetings, another core element typically lasting between 45-60 minutes. The remaining SSCs held longer monthly meetings timed around specific referrals.

12 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Impact on Students

Findings from a range of data sources demonstrate that City Connects has a positive impact on students in Catholic schools. This section first presents findings related to academic achievement and academic readiness. Next, we turn to the impact of City Connects on measures of student thriving.

Academic Achievement in Elementary School

This section reports results from an initial analysis of 2010-11 data from the 14 Boston Catholic schools taking part in City Connects that year and a comparison group of nine elementary schools not taking part in City

Connects.

11 It is important to note that outcome evaluation requires data over several years. The two sources of data typically used to evaluate City

Connects in the public schools are report card scores and standardized test scores (Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System, MCAS). In the Catholic school context, report card content and format varies across schools; the unavailability of a standard report card across schools limits the basis for comparison.

Although MCAS data are not available for Catholic school students,

Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Boston began administering a standardized achievement measure, the Stanford 10 Achievement Test, in grades 2-8 during the 2009-2010 school year. This report presents a comparison of student achievement growth as measured by the Stanford

10 in the subject areas of Mathematics, Reading, and Language. Four years of assessment results (from 2009-10 through 2012-13) were analyzed for students in grades 2-8.

Table 4 presents demographic information on students in the City

Connects and comparison groups for the full Stanford 10 analytic sample across grades.

12

11 Comparison schools were all Catholic elementary schools in six “urban rim” (former industrial) communities surrounding the Greater Boston area.

12 Numbers are smaller than those in Table 1 because students in the SAT-10 analytic sample (grades 2-8 only) are a subset of all students enrolled in City Connects and comparison schools.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

13

Table 4.

Demographic Information, City Connects Catholic and Comparison Schools, Stanford 10

Analytic Sample

Grades 2-8 City Connects Students

(N=3,216)

Comparison Students

(N=2,403)

Gender

Male

Race

Asian

Black

Hispanic

White

Other

Free/Reduced Price Lunch

Registering as Eligible

49%

7%

18%

16%

40%

19%

31%

46%

10%

10%

8%

55%

17%

9%

Data source: Archdiocese of Boston, Catholic Schools Office

As seen in Table 4, City Connects and comparison schools were similar across several characteristics, including gender. They also differ in several important respects. City Connects schools include higher percentages of students of color and higher percentages of students living in poverty, as measured by eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch.

Mathematics.

A statistical analysis that adjusted for demographic differences between City Connects and comparison students found that the average mathematics achievement level in grade 6 was significantly higher for City Connects students than for equivalent peers with similar demographic characteristics. City Connects students also demonstrated a significantly higher rate of growth. As Figure 5 shows, the two groups of students started with similar average scores in grade 3, but City Connects students gained at a higher rate than their comparison peers. By grade 6, the average difference between the two groups was 16 scale score points— more than half a standard deviation. This difference is one-third greater than the size of the achievement gap associated with eligibility for free/ reduced price lunch in this analysis.

14 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Students who remained enrolled in a City Connects school for more years were also more likely, on average, to have additional gains in achievement, compared to those with fewer years of City Connects involvement.

13

Figure 5. Growth in Stanford 10 Math Scores (2009-10 to 2012-13): Model-adjusted Mean

Scores for City Connects Catholic School and Comparison Students

Source: Stanford Achievement Test 10 scores, 2009-10 to 2012-13.

City Connects N=3,216; Comparison N=2,403

Reading. Differences in grade 6 achievement of a smaller magnitude were found for the Stanford 10 Reading assessment, and the difference was not statistically significant. City Connects sixth graders had average Reading scores that were 11 scale score points (39% of a standard deviation) higher than their peers.

13 Figures 5-7 present scores estimated by a hierarchical linear model that controls for student gender, race/ethnicity, having an IEP, and being eligible for free or reducedprice lunch. For City Connects Catholic school students, the figure shows the average growth trajectory for students who began participating in City Connects in grade 3 and remained enrolled in a City Connects school each year through grade 6. Because this analysis is not based on an experimental design, it cannot rule out other factors that might have led to the observed differences between City Connects and comparison students.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

15

Figure 6.

Growth in Stanford 10 Reading Scores (2009-10 to 2012-13): Model-adjusted Mean

Scores for City Connects Catholic School and Comparison Students

Source: Stanford Achievement Test 10 scores, 2009-10 to 2012-13.

City Connects N = 3,182; Comparison N = 2,403

Language. On the Language assessment, sixth graders participating in

City Connects had higher scores on average than their peers in comparison schools (14 scale score points, or half a standard deviation), but the difference was not statistically significant.

This relationship between City Connects participation and achievement was significantly weaker among low-income students compared to others, as indicated by eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch programs. As the two graphs in Figure 7 illustrate, lower-income City Connects students started out with slightly lower average scores in grade 3 than their lower-income peers in comparison schools, but surpassed the comparison students by grade 6. The overall difference in scores for this subgroup in grade 6 was about a quarter of a standard deviation (8 scale score points). Among moderate- or higher-income students (as measured by non-eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch), City Connects participants started out at about the same level as comparison students, but pulled ahead of them by approximately half a standard deviation (15 scale score points) by grade 6. (Note that although higher and lower income students exhibited different patterns, the relationship between City Connects participation and grade 6 results did not reach the level of statistical significance in either group.)

16 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Figure 7. Growth in Model-adjusted Mean Stanford 10 Language Scores (2009-10 to 2012-13) by Free/Reduced-Price Lunch Eligibility

Eligible for Free/Reduced-Price Lunch

City Connects N=1,005; Comparison N=228

Not Eligible

City Connects N=2,211; Comparison N=2,175

Source: Stanford Achievement Test 10 scores, 2009-10 - 2012-13.

The differences between City Connects and comparison schools should be kept in mind as context for understanding these findings. Because all Boston schools in the Archdiocese participate in City Connects, comparison schools are recruited from surrounding cities, which generally have poverty rates lower than that in Boston.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

17

Gender

Male

Female

Missing gender

Race

Asian

Black

Hispanic/Latino

White

Mixed/Other

Missing race

School Readiness in Early Childhood

To better understand the impact of City Connects on pre-school and kindergarten students, City Connects administered the Bracken School

Readiness Assessment (BSRA) in both City Connects Catholic and comparison schools.

14 The BSRA is a widely-used cognitive test for children in pre-K through grade 2 that assesses five basic skills considered essential for school readiness: color naming, letter identification, counting, sizes/comparisons, and naming shapes.

In 2009-10 through 2012-13, the BSRA was administered to both levels of pre-kindergarten and all kindergarten students (referred to as K0, K1, and

K2 in this report, or students aged 3, 4, and 5 years, respectively) in both intervention and comparison schools. All students in the intervention and comparison schools were invited to participate in the evaluation. Table 5 presents demographic information on students in the City Connects and comparison groups for the Bracken analytic sample across grades.

Table 5. Student Demographic Information, City Connects Catholic and Comparisons Schools

(Bracken Analytic Sample)

City Connects Students

(N=1,228)

Comparison Students

(N=580)

49%

51%

9%

24%

16%

37%

12%

4%

51%

36%

13%

12%

15%

9%

52%

4%

8%

Free/Reduced Price Lunch

Registering as Eligible

Data source: Individual schools’ demographic data.

13% 17%

Table 5 summarizes information for the full Bracken analytic sample of

1,808 students. Of these, 1,143 had data from one school year, 575 had data

14 Schools included all schools receiving the City Connects intervention and a comparison group of nine schools. Comparison schools were all Catholic elementary schools in six

“urban rim” (former industrial) communities surrounding the Greater Boston area.

18 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

from two school years, and 90 had data from three school years. Bracken scores are normed in 3-month age groupings and always have a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. Scores within the 85-115 range are considered indicative of “average school readiness.” Scores below 85 or above 115 are considered indicative of “delayed” and “advanced” school readiness, respectively.

In this analysis, we estimated the average point-in-time difference between

City Connects and comparison Bracken scores in a repeated measures context using Hierarchical Linear Models (HLM) methodology.

15 The differences in

City Connects and comparison students’ Bracken scores were estimated after controlling for demographics: gender, race, socio-economic status, initial grade in formal schooling, and cohort. Figure 8 shows the differences in student percentile scores across City Connects and comparison schools, by age.

Figure 8. Difference in Bracken student percentile scores, City Connects Catholic school versus comparison students, by age (2009-10 through 2012-13)

14%

12%

10%

8%

6%

4%

2%

0%

-‐2%

3:0 -‐ 3:3 -‐ 3:6 -‐ 3:9 -‐ 4:0 -‐ 4:3 -‐ 4:6 -‐ 4:9 -‐ 5:0 -‐ 5:3 -‐ 5:6 -‐ 5:9 -‐ 6:0 -‐ 6:3 -‐ 6:6 -‐ 6:9 -‐

3:2 3:5 3:8 3:11 4:2 4:5 4:8 4:11 5:2 5:5 5:8 5:11 6:2 6:5 6:8 6:11

-‐4%

Age (3 month groupings)

In Figure 8, positive numbers indicate that City Connects students are outperforming comparison students. The figure shows that City Connects students begin K0 with slightly lower school readiness than comparison students. However, because longer exposure to City Connects is associated

15 A non-parametric time longitudinal model is utilized to minimize the possibility of model misspecification. This has the practical effect of minimizing potential bias in treatment effect estimates due to inaccurate representation of student trajectories.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

19

with higher relative school readiness, students who are continuously enrolled in City Connects outperform comparison students by the end of

K0. This difference continues to grow over time, becoming statistically significant by the spring of K1.

In percentile terms, City Connects students on average begin approximately 3 percentile points below the comparison students but finish approximately 13 percentile points above comparison students by the end of kindergarten. Thus, holding age and demographics constant, we find that longer exposure to City Connects is associated with higher levels of school readiness. By the spring of the second school year of exposure to the intervention, City Connects students have statistically significantly higher school readiness scores than comparison students.

Student Thriving in Elementary School

During 2012-13, City Connects students in grades 3-5 were administered a survey that measured their perceptions of relationships with peers, their school, and academic subjects. Across the 16 City Connects schools, 734 students (58% of all students in grades 3-5) took part in the survey.

Survey items (20) were drawn from existing measures. Analysis of the results confirmed six major “scales” or dimensions of student thriving.

Four scales address relationships between students and the school

(competence in and attitudes toward math; competence in and attitudes toward reading; perceived relationship with teacher; sense of belonging and membership in school). Two scales address students’ relationships with peers (perceived victimization by bullies; self-reported bullying behaviors). For all scales, higher scores are more positive (e.g., a response of 1 represents a negative feeling, such as “Don’t like at all,” while a response of 5 represents a positive feeling, such as “Like a lot”). Mean scores for the four student-school relationship scales from the 2012-13 survey, by grade, are presented in Figure 9.

20 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Figure 9. City Connects Social Competence Survey, Mean Scores for School Relationship Scales by Grade, 2012-13

5 a b c

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

4

3

2

1

0

Sense of School Membership Rela9onship with Teacher Competence & A@tude: Math Competence & A@tude: Reading a: grade 3 significantly higher than grade 4 (p < 0.05); b. grades 3 and 4 significantly higher than grade 5 (p < .001); c: grade 3 significantly higher than grades 4 and 5 (p < .01);

As Figure 9 shows, third graders scored significantly higher than fourth or fifth graders on all scales except Attitudes Toward Math (p < .05).

Also, fourth graders scored higher than fifth graders on the Teacher

Relationships scale (p<.01). In general, this is consistent with a trend seen in research: scores drop somewhat as children move through the later elementary school grades.

Results from the two peer-relationship scales from the 2012-13 survey, by grade, are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10. City Connects Social Competence Survey, Mean Scores for Peer Relationship Scales by

Grade, 2012-13

5 a

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

4

3

2

1

0

Self-‐Reported Bullying Perceived Vic=miza=on

Note: Higher values represent more favorable scores: less Bullying or Victimization a: grade 3 significantly higher than grade 5 (p < 0.05)

As shown in Figure 10, third grade students reported significantly less bullying behavior than fifth grade students, although little bullying activity was reported at any grade. It is typical that less bullying is reported at lower elementary school grades.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

21

Turning next to a comparison of social competence survey scores across years, Figure 11 displays mean scores for the six thriving scales for school years 2011-12 and 2012-13.

Figure 11. City Connects Social Competence Scale Scores, 2011-12 and 2012-13

5

2011-‐12

2012-‐13

4

3

2

1

0

Sense of School

Membership

Rela9onships with

Teacher

Competence &

A@tude: Math

Competence &

A@tude: Reading

Self-‐Reported

Bullying

Perceived

Vic9miza9on

As seen in Figure 11, while most scores were consistent across time, the level of perceived victimization improved slightly from 2011-12 to 2012-13.

Because scores for four of the social competence scales differ by grade in school (see Figures 9 and 10), it is important to consider whether differences in mean scores from 2011-12 to 2012-13 may reflect grade-related differences in sample composition from year to year. To better understand changes over time, scores for students in grade 5 only were compared across the two years; see Figure 12.

Figure 12. City Connects Social Competence Scale Scores in Grade 5, 2011-12 and 2012-13

5

2011-‐12 (Grade 5)

2012-‐13 (Grade 5)

*

4 *

3

2

1

0

School Membership Rela7onship with Teacher Competence & A?tude:

Math

Competence & A?tude:

Reading

Self-‐Reported Bullying

*Mean difference was statistically significant from previous year (p<.05).

Perceived Vic7miza7on

22 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

As shown in Figure 12, except for Relationship with Teacher and selfrated Reading Competence, which decreased slightly, mean scores for grade 5 students were steady across 2011-12 and 2012-13. This consistency is important in light of the earlier City Connects finding that fifth grade scores had significantly improved from 2009-10 to 2010-11.

16

The results shown in Figure 12 indicate sustained effects in social competence for fifth grade students in City Connects Catholic schools.

Summary of Impact on Students

For both elementary and early childhood students in Catholic schools, results show beneficial impacts of City Connects on measures of academic achievement and thriving. An analysis of standardized test score data (Stanford 10) reveals that the average mathematics achievement level in sixth grade is significantly higher for City Connects students than comparison students, and that they demonstrated a significantly higher rate of growth. Data from a standardized assessment of school readiness show that by spring of the second year of exposure to the intervention, City Connects pre-school students have significantly higher school readiness scores than comparison students, and longer exposure to City Connects is associated with higher levels of school readiness. In measures of thriving, results indicate sustained gains in social competence for City Connects students.

16 City Connects in Catholic Schools Evaluation Summary Report, 2012, pp. 19-21.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

23

Impact on Schools

Principal Satisfaction

In the spring of 2013, City Connects surveyed principals about their satisfaction with the program. Fifteen principals received the survey and

14 completed it. (One of the City Connects schools was in the process of closing at the time of the survey; this principal was not surveyed.) Of those who completed the survey, 100% reported that they were satisfied with

City Connects as a whole, and 100% would recommend City Connects to a principal in another school.

Principals were asked whether they were satisfied with the support the

SSC provides to core groups who participate in the intervention. Responses were unanimous, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Percentage of Principals Satisfied with the Supports the SSC Provides in Each Area*

Students

(e.g., securing services, providing individual support, running lunch groups) 100%

Teachers

(e.g., conducting Whole Class Reviews and assisting with behavior challenges in the classroom)

Families

(e.g., family outreach, following up with families, assisting with parent meetings)

100%

100%

Principals

(e.g., coordinating Student Support Team, supporting administrative activities)

The School

(e.g., their presence on the playground, bus and lunch duty)

Community Partnerships

(e.g. maintaining communication with agencies, following up to secure services, coordinating agency work in the school)

100%

100%

100%

*Not all principals responded to every item. Source: City Connects 2013 principal survey.

Thirteen principals responded to an open-ended item about City Connects benefits: “What was the most valuable thing about having City Connects in your school this year?” Responses fell into several categories, including

(i) review, support, and services for all students, (ii) supports to teachers, principals, and families in addition to students, and (iii) community partnerships. Example responses include:

“The Whole Class Reviews make sure that no child slips through.”

“We were able to offer more students more services because of our partnership with City Connects.”

24 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

“SSC was wonderful… has a hands on approach. Always present to students, faculty and principal.”

“[The most valuable thing was] the numerous outside resources secured by our coordinator.”

Twelve principals responded to an open-ended item about City Connects areas for change: “How could City Connects improve its value in your school (or other schools) in the future?” Some principals made recommendations for deepening the work by promoting the growth of advanced SSCs, for example through tailored professional development.

Others noted the current need for supports to the early childhood population (e.g., “ More early childhood [professional] development for Principals and Coordinators. The program is very beneficial and needed within our schools.” ) Finally, some principals did not observe areas for improvement, and instead called for continued funding and implementation of the program (e.g., one principal simply stated,

“Continue on,” and another reported, “…we are 100% satisfied with the value City Connects brings to our school.” )

Teacher Satisfaction

The most recent teacher satisfaction survey was conducted in the spring of

2011.

17 The majority of teachers (86%) were satisfied with the City Connects intervention and 84% would recommend the program to other schools.

Teachers were also asked to rate their satisfaction with the support City

Connects provides for various school areas; see Table 7.

Table 7. Percentage of Teachers Satisfied with City Connects Support for Students, Teachers, and the School

Overall Satisfaction with City Connects Support for:

Students (e.g., securing services, providing individual support, running lunch groups)

2010-11:

Satisfied

Teachers

94%

Teachers (e.g., conducting Whole Class Reviews, assisting with behavior challenges in the classroom)

The School (e.g., coordinating the Student Support Team, outreach to families, partnering with community agencies, their presence on the playground)

97%

94%

17 Of the full set of teachers invited to participate, 149 responded; not every teacher responded to every question.

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

25

Teachers generally reported that instructional practices, classroom behavioral management, and relationships with families all were strengthened by the use of the City Connects model. Table 8 highlights the perceived impact of City Connects in several specific areas of practice across the three years of the intervention.

Table 8. Percentage of Teachers Agreeing with Statements of Impact on Teachers’ Practice,

2008-09 to 2010-11

Impact on Teachers’ Practice

2008-09:

Strongly/

Somewhat

Agree with

Statement

2009-10:

Strongly/

Somewhat

Agree with

Statement

2010-11:

Strongly/

Somewhat

Agree with

Statement

Whole Class Reviews offered me new options for working with students in my classroom.

65% 73% 86%

School Site Coordinator supported me with consultation on the behavior of one or more students in my class.

84% 91% 79%

School Site Coordinator connected my students to services both within the school and in the community.

School Site Coordinator intervened in crises connected with students.

City Connects has been helpful in making my classroom conducive to learning.

City Connects has been helpful with the behavior of my students.

City Connects has been helpful with increasing my ability to address students with unique needs (i.e., special educational needs).

City Connects has been helpful in increasing the time I have to focus on instruction.

53%

53%

84%

81%

65%

66%

70%

65%

84%

79%

73%

70%

69%

73%

87%

100%

100%

76%

As seen in Table 8, overall, teachers agreed that City Connects impacts a variety of areas of their practice. In most categories, percentages of agreement rose in 2010-11. The only category with a substantive drop in agreement from 2009-10 to 2010-11, “School Site Coordinator supported me with consultation on the behavior of one or more students in my class,” may actually reflect a hidden gain: having had City Connects in place for several years, teachers may feel further supported and equipped to address behavior needs themselves. This would cohere with the fact that 100% of the teachers participating in the survey reported that City Connects had a positive impact on the behavior of students in 2010-11, an increase from

79% in 2009-10. A drop in the need for consultation on behavior issues

26 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

would also cohere with the finding that all responding teachers reported that they felt better equipped to provide services to students with unique needs. Overall, teachers felt that City Connects helped make the classroom more conducive to learning, allowing for better academic success.

In their open-ended comments, teachers reported they have more options for addressing individual needs of students. One teacher noted, “City

Connects helps us to track a student in social/emotional/educational progress and to address problems quickly and effectively.” Teachers also discussed a positive change in the work environment, citing increased collaboration, sense of community, and a shared goal to meet students’ needs. One teacher enjoyed “knowing that there is a support system in place that helps teachers handle problems better and lets teachers know they do not have to go [at] it alone.”

Table 9 shows the percentage of teachers who agreed that City Connects supported them in various specific areas of their work serving students’ needs.

Table 9.

Percentage of Teachers Reporting Helpfulness of City Connects Intervention in

Addressing Students’ Needs

Impact on Teacher’s Work Serving Students’ Needs

2008-09:

Very/Somewhat Helpful

2009-10:

Very/Somewhat Helpful

2010-11:

Very/Somewhat Helpful

I became more aware of the range of services that could help my students.

78% 85% 61%

City Connects enhanced teacher connection with students’ families.

School Site Coordinator provided support for my relationships with families.

School Site Coordinator listened when I needed someone to talk with regarding issues in my classroom.

I was satisfied with the accessibility of quality services for students.

71%

57%

88%

80%

68%

66%

91%

88%

85%

69%

83%

87%

As shown in Table 9, in 2010-11, 85% of teachers reported that City

Connects facilitated a connection between the teacher and the students’ families (up from 68% the previous year). A majority of teachers reported that SSCs were helpful in listening to issues regarding their classrooms, and 87% felt satisfied with the accessibility of quality services available for students. A point of future improvement to highlight may be the teachers’ awareness of services available to students: only 61% of teachers felt they became more aware of the range of services, down 24% from the previous

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

27

year. Another possible interpretation of this finding is that after several years with City Connects, teachers are already aware of many of the services that could benefit their students, and that awareness does not need to expand as much over time.

Respondents stated:

“City Connects puts the needs of the student at the top of a priority list.”

“Fewer children are falling through the cracks.”

“Students receive coordinated attention in a timely manner and their progress is carefully tracked.”

Summary of Impact on Schools

Principals and teachers reported high levels of satisfaction with

City Connects. Principals reported that they particularly valued the reviews of all students and the services and the increase in services and resources for students. Teachers especially endorsed City Connects’ support with behavior and with their ability to address unique needs of students. Both principals and teachers reported that City Connects contributes to a culture of collaboration and shared purpose in addressing students’ individual needs.

Impact on Community Partners

In 2012-13, City Connects Catholic schools collaborated with 190 community partners. The expansion in range and number of partnerships has been a central focus of implementation in the past several years.

School Site Coordinators were charged with increasing connections with community services, including after-school programs, enrichment opportunities, mental health counselors, summer camps, tutors, mentors, and providers of family services.

Table 10 lists community partners for 2012-13.

28 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Table 10.

City Connects in Catholic Schools, Active Community Partners, 2012-13

826 Boston

ABCD - Dorchester Neighborhood

Service Center

Arbour Counseling

Bay State Fencers

Boston Centers for Youth and

Families

Nazzaro Community Center

Orchard Gardens Community Center

Best Dental of Wellesley

Big Brother/Big Sister

Bird Street Community Center

Blessed Mother Teresa Parish

BOKS (formerly Fit Kidz)

Boston City Singers

Boston College

First Year Service Program

Lynch School of Education: Roche

Center for Catholic Education

School of Social Work

Boston Institute for Psychotherapy

Boston Medical Center

Boston Police Department

G.E.A.R. Program

Boston Public Library

Boston Public Schools

Boston School of Music Arts

Boston Stars Hockey

Boston Tae Kwon Do Academy

Boston University

Phonics Program

Sibling Program

Boy Scouts of America: Boston

Minuteman Council

Boys & Girls Club

Blue Hill

Charlestown

South Boston

Yawkey of Roxbury

Boys and Girls Clubs of Dorchester

Walter Denney Youth Center

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Cardinal Scholars

Cathedral High School

Central Park Lanes

Champion Tae Kwon Do

Charles River Aquatics

Charlestown Youth Hockey

Chelsea Community Schools

Children’s Hospital Boston

Commonwealth History Museum

Cradles to Crayons

Curtis Hall Community Center

Department of Child and Family

Services (DCF)

Dorchester House Multi-Service

Center

Earthen Vessels

East Boston Girls Softball League

Education Collaborative (EDCO)

Ellis Memorial and Eldredge House,

Inc.

Emerald Necklace Martial Arts

Emerson College

Emmanuel College

Franciscan Hospital for Children

Girl Scouts of Eastern Massachusetts

Girls LEAP Self-Defense, Inc.

Hale Reservation - Hale Summer

Day Camp

Harvard University - The Arnold

Arboretum

Home for Little Wanderers

Joslin Diabetes Clinic

Junior Achievement

Life Dimensions Neuropsychological

Services

Little People’s Playhouse

Malden Catholic High School

Malden-East Boston Youth Hockey

Massachusetts General Hospital

MassArt - Artward Bound

MetroLacrosse

Nazzaro Center

Neighborhood Children’s Theatre, Inc.

North Suffolk Mental Health

Association

Northeastern University - Service

Learning

OTA Watertown Koomar Center

Paris Street Community Center

Parkway Dance

Parkway Sports

Peace First

Polished, LLC

Pop Warner Football Conference of

Eastern Mass.

Porrazzo Skating Rink Ice Skating

Rink

Private Tutoring

Project DEEP

Roslindale Arts Center

Sacred Heart School Dance Program -

Samia DeSimone

Salesian Boys & Girls Club of East

Boston

Salvation Army

Kroc Corps Community Center

South End Corps

Saugus Youth Soccer Association

Simmons School of Social Work

South End Community Health Center

Sportsmen’s Tennis Club

St. Rose School Counsel

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church

Steppingstone Foundation

College Success Academy

Strong Women, Strong Girls

Suffolk County District Attorney

Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department-

Choice Program

Super Soccer Stars

Sylvan Learning Center

The Forsyth Institute

Tufts Medical Center

United South End Settlements

Urban Improv

Verve Yoga

Winthrop Gymnastics Academy

Winthrop School of Performing Arts

Winthrop Youth Hockey

YMCA

Charlestown

Dorchester

East Boston

Huntington Ave

Hyde Park

Roxbury

Zumix

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

29

“We were able to have at-risk students referred to our program smoothly. Our contact at the school was effective at keeping in touch with us and responding to any concerns we had.”

–City Connects Community partner

Conclusions and Future Implications

In 2012-13, City Connects in Catholic Schools has demonstrated positive impacts on students, schools, and community partners. Through the collaboration of all the partners, City Connects has linked students to services tailored to their individual strengths and needs. The model has been implemented with fidelity, and strong partnerships with community agencies have been built.

Benefits to students are reflected in measures of academic achievement at the elementary school level and in measures of school readiness in preschool and kindergarten. Principals and teachers report the beneficial impact of City Connects on their work.

The evaluation findings of City Connects suggest continued success in implementation of the City Connects model of optimized student support in participating Catholic elementary schools. The evaluation has identified several areas for continued improvement:

• With the new availability of standardized (Stanford 10) test scores for City Connects and comparison students, City Connects will continue to track progress in academic achievement across schools.

• Through use of an electronic data collection and management system (SSIS, developed by City Connects), School Site

Coordinators will continue to strengthen partnerships with community agencies and fill gaps in service provision by developing and tracking new partnerships.

• City Connects will continue to improve professional development meetings by widening offerings (especially in the area of early childhood) and drawing on participants’ knowledge to uncover new ways support the practice in individual schools.

• City Connects will continue to evaluate and share best practices that SSCs may find useful in their daily work within schools.

• City Connects will continue its work with the Better Way

30 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Foundation and community agencies to help appropriately serve the unique needs of the early childhood population now being served by the City Connects model.

“A culture of problem-solving has emerged in our staff.”

—City Connects Catholic School Teacher

“There [is] not a doubt in my mind that our school is a better place because of our Site Coordinator and this program.”

–City Connects Catholic School Principal

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

31

References

Bertelsmann Foundation. (2011). Social justice in the OECD – How do the member states compare?

Sustainable governance indicators 2011 . Gütersloh,

Germany: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Blow, C. M. (2011, October 28). American’s exploding pipe dream. The

New York Times . Retrieved November 22nd, 2011 from http://www.

nytimes.com/2011/10/29/opinion/blow-americas-exploding-pipe-dream.

html?_r=2&hp

Bryk, A.S., Sebring, P.B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q.

(2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago . Chicago:

Chicago University Press.

Cattaro, G. M. (2002). Catholic schools: Enduring presence in urban

America. Education and Urban Society , 35, 100-110.

Dearing, E. (2008). The psychological costs of growing up poor. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (Special Issue: Scientific Approaches to

Understanding and Reducing Poverty, S. G. Kaler & O. M. Rennert, Eds.),

1136, 324-332.

Fenzel, L. M., & Domingues, J. (2009). Educating Urban African American

Children Placed At Risk: A Comparison of Two Types of Catholic Middle

Schools. Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice , 13, 30-52.

Hursh, N., DiNatale, P., & Walsh, M. (2010) . Report on City Connects in

Dayton Catholic Schools: 2010 . Boston College: Center for Optimized

Student Support.

Hursh, N., DiNatale, P., & Walsh, M. (2011). Report on City Connects in

Dayton Catholic Schools: 2011 . Boston College: Center for Optimized

Student Support.

Kahn, C. B. & Martin, J. K. (2011). The measure of poverty: A Boston

Indicators Project special report . Boston: The Boston Foundation.

O’Keefe, J. M., & Scheopner, A. J. (2009). Bridging the gap: Urban Catholic schools addressing educational achievement and opportunity gaps in the

United States. International Studies in Catholic Education , 1, 15-29.

Phillips, M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G., Klebanov, P. & Crane, J. (1998).

Family background, parenting practices, and the black–white test score gap. In C. Jencks and M. Phillips (Eds.), The black-white test score gap .

Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

32 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

Rothstein, R. (2010). How to fix our schools. Issue Brief #286. Washington,

DC: Economic Policy Institute, October 14, 2010. Available: www.epi.org.

Tavernise, S. (2012) Education gap grows between rich and poor, studies say. New York Times , February 9, 2012.

Walsh, M.E., & DePaul, G. (2008). The essential role of school-community partnerships in school counseling. In H. L. K. Coleman & C. Yeh

(Eds.), Handbook of school counseling (pp. 765-783). Baltimore: MidAtlantic

Books & Journals.

Appendix A.

City Connects in Catholic Schools Personnel

Executive Staff

Mary E. Walsh, Ph.D., Executive Director of City Connects

Matthew J. Welch, Ed.M., Program Director of City Connects in Catholic

Schools (2011–13)

School Professionals

Cathedral Grammar School

Sr. Dorothy Burns, CSJ, Principal

Joan Jackson, School Site

Coordinator

East Boston Central Catholic

School

Maryann Manfredonia, Principal

Caitrin O’Rourke, School Site

Coordinator

Holy Name Parish School

Lynne Workman, Principal

Dan Hurley, School Site

Coordinator

Mission Grammar School

Maura Bradley, Principal

Albert Hayle, School Site

Coordinator

Pope John Paul II Catholic

Academy, Columbia

Claire Barton Sheridan, Principal

Sarah Cochran, School Site

Coordinator

Pope John Paul II Catholic

Academy, Lower Mills

Kim Mahoney, Principal

Lisa Warshafsky, School Site

Coordinator

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

33

Pope John Paul II Catholic

Academy, Mattapan Square

Lou Ann Melino, Principal

Priya Venkatakrishnan, School

Site Coordinator

Pope John Paul II Catholic

Academy, Neponset

Kate Brandley, Principal

Amanda Reyes, School Site

Coordinator

Sacred Heart School

Monica Haldiman, Principal

Sr. Marie Connolly, CSJ, School

Site Coordinator

South Boston Catholic

Academy

Nancy Carr, Principal

Tim Lewis, School Site

Coordinator

St. Brendan School

Maura Burke, Principal

Britta Ashman, School Site

Coordinator

St. John School

Karen McLaughlin, Principal

Caitrin O’Rourke, School Site

Coordinator

St. Patrick School

Mary Lanata, Principal

Katie Horan, School Site

Coordinator

St. Mary of the Assumption

School

Maureen Jutras, Principal

Alicia Rainwater, School Site

Coordinator

St. Rose School

Caitlin Keeton, Principal

Peter MacNeil, School Site

Coordinator

St. Theresa of Avila School

Jane Gibbons, Principal

Dan Fitzgerald, School Site

Coordinator

Research Staff

Sarah Backe, Graduate Assistant

Amy Orecchia, Graduate Assistant

Stephanie Sienkiewicz, Graduate Assistant

Ashley Gilbert, Undergraduate Intern

Maggie Ryan, Undergraduate Intern

34 ©2014 Trustees of Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

City Connects in Catholic Schools is a collaborative partnership between the Catholic Schools Foundation, Boston College, and community-based organizations to link more than 4,000 students to the services and resources they need to thrive and to be academically successful. This program is currently in 16 Catholic elementary schools in the Archdiocese of Boston.

City Connects in Catholic Schools is based at the Center for Optimized

Student Support at the Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

Please direct all inquiries regarding this report to:

Mary Walsh, Ph.D.

Executive Director, City Connects

Kearns Professor of Urban Education & Innovative Leadership,

Lynch School of Education

Boston College

Campion Hall, Room 305D

140 Commonwealth Avenue

Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 www.bc.edu/cccs

Printed by Boston College

JUNE 2014

City Connects in Catholic Schools • Evaluation Report 2014

35