IMPLEMENTATION OF PROGRAM POLICY BY INDIVIDUALS: BATEMAN (1971)

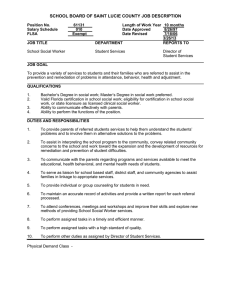

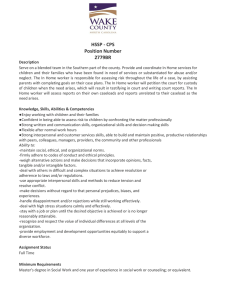

advertisement