BOSTON COLLEGE L S E

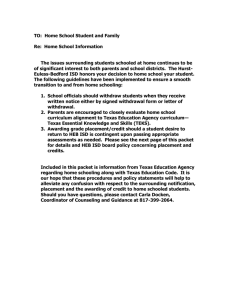

advertisement