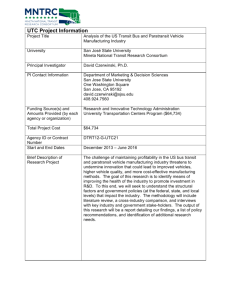

Determining Relationships and Policies that Transit Properties... Employers to Increase Ridership

advertisement