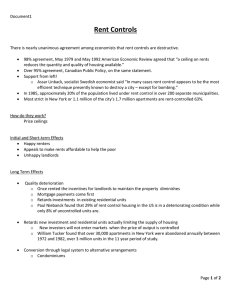

AND Carol Jane Spack 1976 URBAN

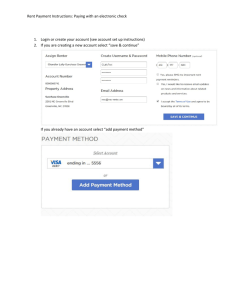

advertisement