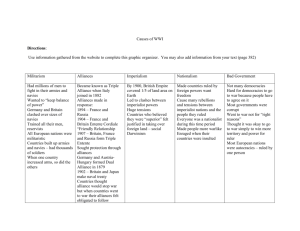

PEOPLE OF COLOR IN ALLIANCE by

advertisement