WHERE ARE THEY NOW?: HOMELESS A. NOVAK Bachelor of Arts

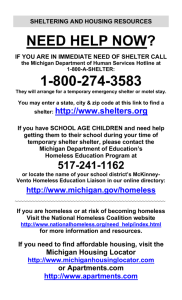

advertisement