Document 11264117

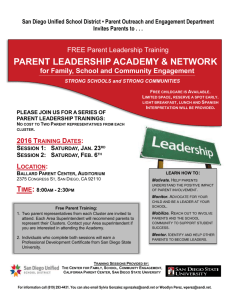

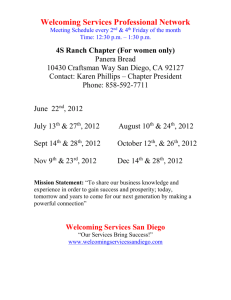

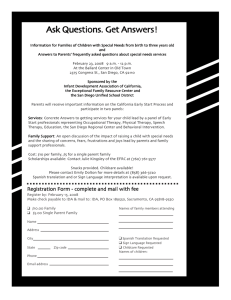

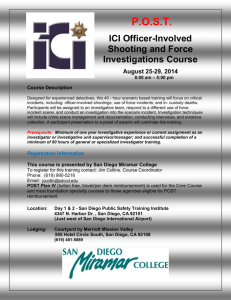

advertisement