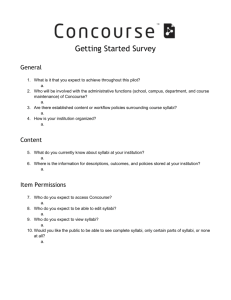

A STUDY by (1970) CONCOURSE

advertisement