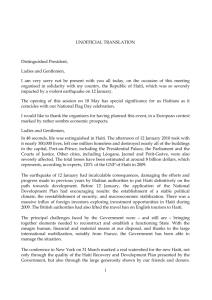

2011 JUN 30 ARCHIVES

advertisement