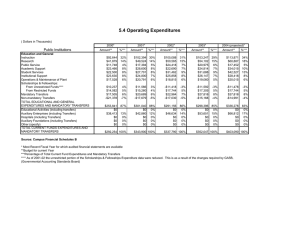

AN ANALYSIS OF EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT INTERGOVERNMENTAL TRANSFERS IN INDIA

advertisement