2012-2013 Annual Report

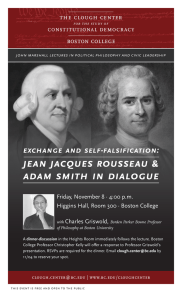

advertisement