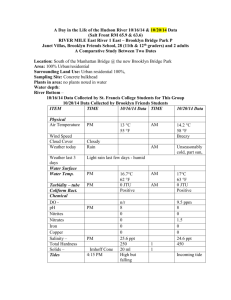

The New Partner on the Block: ... Arts and Cultural Organizations in Community Economic...

advertisement