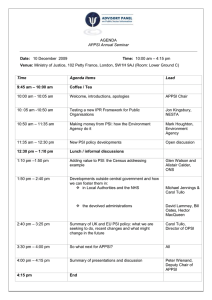

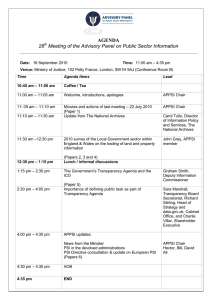

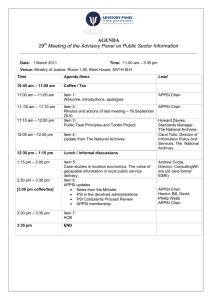

The impact and success of legislation on the re-use of... sector information

advertisement