What is the Value of Open Data?

advertisement

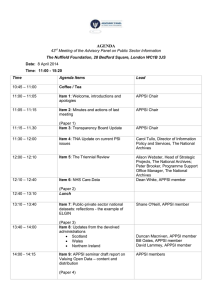

What is the Value of Open Data? Open Data is defined as “Data which can be used, re-used and re-distributed freely by anyone - subject only at most to the requirement to attribute and share-alike. There may be some charge, usually no more than the cost of reproduction”. Source: APPSI Glossary http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/appsi/appsi-glossary-a-z.htm The glossary is also available in wiki form at http://data.gov.uk/blog/appsi-glossary-terms-opendata-and-public-sector-information Proceedings of an APPSI Seminar on 28 January 2014 Edited by David Rhind This document is Crown Copyright and is published under the UK Open Government Licence. It may be reproduced in whole or part in any medium provided only that the contents are not modified and that citation is made to the source. 1 About APPSI The Advisory Panel on Public Sector Information (APPSI) was established as a NonDepartmental Public Body by Douglas Alexander MP, Minister for the Cabinet Office in April 2003. In October 2006, APPSI became a Non-Departmental Public Body of the Ministry of Justice (then the Department of Constitutional Affairs). APPSI terms of reference These apply to England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and are to: review and consider complaints under the reuse of public sector information regulations 2005 (SI 2005 No. 1515) and advise on the impact of the complaints procedures under those regulations; advise Ministers on how to encourage and create opportunities in the information industry for greater reuse of public sector information; and advise The National Archives and Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office—an official within The National Archives—about changes and opportunities in the information industry, so that the licensing of Crown copyright and public sector information is aligned with current and emerging developments. APPSI’s strengths APPSI has a statutory role in relation to the review process regarding the re-use of Public Sector Information which is not duplicated by any other body. Its (unpaid) members are drawn from the public, private and academic sectors, have good international connections and have a wide range of expertise and practical experience (as lawyers, economists, technologists, data producers (e.g. in health), scientists and business data users, etc) usually at senior level. The range of expertise in APPSI members and alumni is probably unique, enhancing advice to government. Its role embraces the whole UK unlike other bodies concerned with Open Data. The members are non-partisan. They are also independent except for those deliberately appointed to represent Trading Funds and the devolved administrations. APPSI has produced high-quality recommendations which have anticipated and been reflected recently to a remarkable degree in the Government Open Data White Paper, the Shakespeare Review and Government’s Response to the latter. Thus APPSI has also been a catalyst for many of the developments taken forward by the UK Government in recent years. A summary of APPSI impact is at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/meetings/appsi-impact-2013.pdf Finally, APPSI has always followed an approach which is forward looking, based upon constructive critiques and strong public support as appropriate. It has eschewed ‘grandstanding’ and has actively engaged with other bodies to influence and support them. APPSI has never sought to claim credit: it has taken the view that what matters is progress in shaping and implementing effective policy on Public Sector Information/Open Data. 2 Foreword Open Data (OD) has become a major development over the last few years, in the UK and many other countries. The Introduction to this report summarises a number of background issues relevant to Open Data. It is deliberately written to enable non-experts to follow the points made in a seminar of experts convened by APPSI; these points form the bulk of this report. The aim of this seminar was to identify the value – preferably in quantitative (and especially monetary) terms - of Open Data. The structure of the event is replicated in this report. In essence, we pre-circulated a set of thoughts and provocations before the seminar to stimulate thinking then, on the day, had a series of presentations. After each one, a discussant gave immediate personal feedback and an open discussion ensued amongst APPSI members and their guests. That discussion is summarised for each contribution by two APPSI members. Finally at the end of all debates, one guest drew together what he thought were the lessons from all the contributions and discussions. The views expressed at the seminar (and herein) are those of individuals. Characteristically for a field at an early stage of development, opinions differ on a number of key points. Some of the presentations contained many slides. A brief summary of all of them is included and the slides themselves are embedded in the document for ease of access and completeness. I am very grateful to all those who participated in our seminar. A list of all those attending is at Appendix 1. In particular the contributors, discussants, and rapporteurs are owed a special vote of thanks. I am very grateful to McKinsey& Co and especially to Richard Dobbs for making available their splendid facilities at no cost. As ever, we are grateful to The National Archives staff – especially Beth Watson – for their help in the operational aspects of the seminar. David Rhind April 2014 3 Contents Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Pre-circulated paper: Assessing the real benefits of Open Data: a paper to stimulate discussion at the APPSI seminar on 28 January 2014 David Rhind and Hugh Neffendorf, with contributions from other APPSI members 3. Evidence for benefits of Open Data: Open Data User Group Case studies Heather Savory - Open Data User Group Discussant: Simon Briscoe – Advisor to Public Administration Select Committee Report of the discussion: Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven - APPSI 4. The Power of Open Data to Unlock Value Creation Michael Chui - McKinsey & Co. Report of the discussion: Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven - APPSI 5. Example 1: Ordnance Survey review of OS OpenData costs and benefits Neil Ackroyd - APPSI/Ordnance Survey Discussant: Bob Barr, APPSI member Report of the discussion: Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven – APPSI 6. Example 2: The Census as Open Data – costs and benefits Alistair Calder and Neil Townsend, Office for National Statistics (ONS) Discussant: Keith Dugmore – APPSI Report of the discussion: Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven - APPSI 7. Example 3: Transparency and Open (Transport) Data Nick Illsley, Department for Transport Discussant: Hugh Neffendorf, APPSI Report of the discussion: Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven APPSI 8. Key messages and summary of overall points made Andrew Stott, Public Sector Transparency Board Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven APPSI Appendix 1: Attendees at the Seminar 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The concept and practice of Open Data has become rapidly accepted since its early stages in the mid-2000s (ignoring the long standing US federal government practice of what is effectively Open Data and the pioneering Invest to Save scheme in UK which led to the removal of charges for Population Census data in 2001). 2. The developments have been characterised by extraordinary enthusiasm, energy and innovation on the part of entrepreneurs, as well as support by the current and previous Prime Ministers, the Cabinet Office Minister and some government departments. 3. All of this is despite the inherent difficulty of measuring benefits arising from Open Data. This difficulty arises from many factors. Thus previous assessments have been focused on various different aspects of Open (and related) Data, used different data classifications and terminology, and pertained to different geographies and moments in time. Rarely is the availability of Open Data the single key factor enabling success: other factors like financing, customer interest in the service, marketing, and competition matter. Given the very nature of Open Data, tracking its usage is usually difficult and benefits do not always arise where costs are incurred. 4. As a result, it is impossible to put a meaningful single monetary value on the benefits which will be generated through the exploitation of Open Data. We see the monetary estimates frequently banded about as highly speculative. But benefits certainly do exist and are most easily identified by case studies. The big danger lies in heroic extrapolation of these to some overall benefit. 5. The evidence to date suggests that the greatest benefits from Open Data accrue to consumer surplus, especially in the transport domain where time saving by users of apps in planning or making journeys is a major benefit. Other benefits to the end user include some improvement in obtaining best value for money in purchasing goods on-line, other forms of convenience (such as grocery deliveries) and possibly environmental benefits. 6. As yet we know of no major individual cases in the UK where significant numbers of jobs have been created though in aggregate the Open Data sector has certainly generated an unknown number of system development jobs. 7. Given all that has happened to date, it would be surprising if some SMEs working did not become highly successful through exploitation of Open Data though – on past experience – more will fail for a multiplicity of reasons (e.g. access to finance, poor management, inadequate marketing or bad luck). It also seems likely that many of these successful or high potential entities will be bought out by major US firms since they characteristically are prepared to pay more than is normal in the European marketplace. The seminar’s discussions included wider issues relevant to the longer term beneficial development in use of Open Data. Conclusions drawn from them are summarised below. 8. For government the big issue is how best to get the Open Data movement to a selfsustaining level. This involves recognising the existence of the new information 5 ecosystem, with various interacting components and agents. Simply making available data is – as was stressed in the seminar – a necessary but not sufficient condition for success. Central to success is ensuring the on-going health of the National Information Infrastructure (NII), a concept first described by APPSI in 2010. This is the totality of key data sets which are required to underpin the UK economy and government activities- and which accordingly have to be prioritised. Government has done some work on the NII but it needs greater focus to create material benefit. 9. In planning future developments, government has to recognise the reality that major players with massive resources like Google have created universal and widely used platforms. Indeed many users wish to have access to Open Data in formats which are immediately usable with these commercial and proprietary platforms, rather than in the Open Formats on which the star rating system backed by government is based. Explicit collaboration with such players might be inevitable as well as beneficial. 10. There remains an issue about how government should make available Open Data – in as ‘raw’ a form and as early as possible or in more quality-assured and welldocumented a form. This should be driven by user views, recognising different views amongst different classes of users. Such a variegated approach requires good understanding of (sometimes latent) user needs and appropriate resources. 11. To add to the complexity, the Open Data world continues to change rapidly. Michael Chui (see section 4) stresses the spectrum of Open Data sources – including, in his view, commercial and not-for-profit ones as well as governments. APPSI members have witnessed much greater exploitation of government and other-source data in combination (the so-called co-mingling) than was true even a short time ago. 12. The UK is presently a world leader in Open Data concepts and practice. Yet in one respect it is also very different to some other countries. This is because we operate a mixed model. Much government-sourced data is openly available and re-usable under the Open Government Licence but certain other data is charged for and certain government bodies operate under Trading Fund models which effectively require them to pay their own way through providing services or leasing data. The pros and cons of this arrangement have been debated for at least 30 years but as more and more data from multiple sources is used in combination the licensing difficulties under this model will grow, not least because of the difficulty of establishing who owns what share of the resulting Intellectual Property Rights. 6 1. Introduction The last decade or so has seen revolutionary changes in the technology of data collection, analysis and dissemination. The data and information collected by governments, the private sector and voluntary sectors and individuals have shifted dramatically from being collected and held in analogue (e.g. paper) form to being stored digitally. In 1986 around 99% of all information was stored in analogue form; by 2007 some 94% was being stored in digital form1. Moreover the total amount of data has grown exponentially: it has been estimated that more data was harvested between 2010 and 2012 than in all of preceding human history2. This increase owes much to a wide variety of new technologies of data collection (notably video recordings, plus sensors built into satellites, retail outlets, refrigerators, and other platforms) and of processing and dissemination. As a result, the range of data types being collected has also expanded. The OECD3 has identified six categories of new data which can help us to “understand the human condition”. These are set out below. A Data stemming from the transactions of government, e.g. tax and social security systems. B Data describing official registration or licensing requirements. C Commercial transactions made by individuals and organisations. D Internet data, deriving from search and social networking activities. E Tracking data, monitoring the movement of individuals or physical objects subject to movement by humans. F Image data, particularly aerial and satellite images but including land-based video images. But the reality is even more complex: some data are collected by a mixture of means, such as by commercial imaging and crowd sourcing. Thus the Tomnod programme run by DigitalGlobe, a major US supplier of high resolution satellite imagery, invited any individual to scan randomly presented DigitalGlobe images from 1800 square miles of the South Indian Ocean and tag possible wreckage from the Malaysian Airways flight MH370. This information was then passed on to the relevant authorities. Another example of the diversity of data types are the daily reports of the results of new questionnaire-based surveys in the media, some of which give minimal details of how the (often questionable) results were obtained. Much of all this plethora of data informs a multitude of decisions and it shapes attitudes and opinions of government Ministers, business people and the lay public. 1 Hilbert M and Lopez P (2011) The world’s technological capacity to store, communicate, and compute information Science 332 no. 6025 , 60-65 2 This claim is normally attributed to IBM but see http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-17682304. Much of the data is user-collected (e.g. videos and photographs, emails, and social media traffic including tweets). 3 http://www.oecd.org/sti/sci-tech/new-data-for-understanding-the-human-condition.pdf 7 1.1 Open Data Perhaps the earliest form of Open Data was that released by the US federal government. The decision to do this was not rooted in economic assessments. Rather it was founded on Jeffersonian concepts of the benefits of sharing data4 and the democratic importance of citizens having ready access to the information held by their government. A different view has been held at various times in the UK: as long ago as 1817, government published a warning in the London Gazette that anyone making unauthorised use of Ordnance Survey mapping would be prosecuted. Much later there were various economic studies which sought to show that – based on sometimes heroic assumptions – substantial economic benefits would accrue to the state and to commerce from freeing access to and re-use of such data5. Some examples exist of success claimed by government departments. A good example is that of the population census. The data was made available at a high price and under-utilised until the 2001 census when the Census Access Project (supported by the Invest to Save Budget) allowed all users to have free availability. The growth in take-up was unquestionably substantial, allowing for better planning and services, allocation of resources and research. The successful policy continued unquestioned for the 2011 census and considerable evidence of usage and benefit has been gathered to support the Beyond 2011 project. New technology has been a necessary but not sufficient condition for bringing about the revolution. To have maximum effect, the data must be readily and cheaply accessible with simple licensing, the tools to analyse it must exist and human capital must be adequate. Just as important, governments must change many of their prior policies and patterns of behaviour. In the short term at least, government bodies also face some increased cost burdens in making the data ready for wider use. Perhaps the earliest form of Open Data was that released by the US federal government. The decision to do this was not rooted in economic assessments. Rather it was founded on Jeffersonian concepts of the benefits of sharing data6 and the democratic importance of citizens having ready access to the information held by their government. A different view has been held at various times in the UK: as long ago as 1817 government published a warning in the London Gazette that anyone making unauthorised use of Ordnance Survey mapping would be prosecuted. Much later there were various economic studies which sought to show that – based on sometimes heroic assumptions –substantial economic benefits would accrue to the state and to commerce from freeing access to and re-use of such data7. Some examples exist of success claimed by government departments. A good example is that of the population census (see above). 4 As articulated, for example, by Jefferson’s comment that “He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.” 5 Vickery, ibid 6 As articulated, for example, by Jefferson’s comment that “He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.” 7 Vickery, ibid 8 In very recent times attempts have been made in the UK to quantify such potential benefits more precisely, notably by the National Audit Office8 and by the BIS-sponsored review of OS OpenData9. These suffered from being somewhat premature in assessing the value of Open Data in the UK. It is now however commonplace for consultants to produce estimates of potential gains from all of Open Data, sub-sections of it or by commercial sectors which mingle OD and their own data10. These beg questions about what we consider a benefit – as discussed in various parts of this report. The growth of the Open Data and Open Government movements over the period since c.2008 has been remarkable. President Obama launched an Executive Order authorizing Open Data on his first day in office in 2009: the number of OD sets in the USA has risen from 47 in March 2009 to over 90,000 in late 2013. In Britain a set of bodies to represent the user needs in relation to additional data sets, and to carry out research and entrepreneurial activities with start-ups, was set up. Well over 10,000 datasets have been made available in the UK as Open Data under a standard, simple Open Government Licence. Related and contemporary developments have also taken place in many other countries. Perhaps the most obvious demonstration of the internationalization of the Open Data movement is the charter signed by the leaders of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States at the G8 meeting in June 2013. This commits those nations to a set of principles (‘Open by default’, ‘Usable by all’, etc), to a set of best practices, including metadata provision, and national action plans with progress to be reported publicly and annually. Other global bodies – notably the World Bank and the UN Economic Statistics Directorate plus some US states and cities around the world - have also committed to the principles of Open Data and enhanced access to their data stores. Several different ways of describing the potential benefits of Open Data have been used. A convenient shorthand of four potential benefits is: enhanced transparency and government accountability to the electorate, improved public services, better decision-making based on sound evidence, and enhancing the country’s competitiveness in the global information business. 1.2 The value for money of Open Data Given the scale of contemporary data collection, the early stage of realisation of benefits and the efforts being invested by many players, it is not surprising that questions of value for money have been raised. In very recent times attempts have been made in the UK to quantify such potential benefits more precisely, notably by the National Audit Office11 and by the BIS sponsored review of OS OpenData12. These suffered from being somewhat 8 http://www.nao.org.uk/report/implementing-transparency/ ConsultingWhere, ibid 10 Oxera 2012, Deloitte 2012, McKinsey 2013, ibid 11 http://www.nao.org.uk/report/implementing-transparency/ 12 ConsultingWhere, ibid 9 9 premature in assessing the value of Open Data in the UK. It is now however commonplace for consultants to produce estimates of potential gains from all of Open Data, sub-sections of it or by commercial sectors which mingle Open Data and their own data13. These beg questions about what we consider a benefit –as discussed in the main body of the paper. This report summarises a seminar organised and led by APPSI but held in the premises of McKinsey Co in London with the active engagement of experts from many other organisations. Our aim was to seek to identify the benefits – monetised if possible – from the creation and use of Open Data. Our main focus was on the UK but examples from other countries were included. 1.3 Terminology The data revolution has involved contributors from many disciplines in the UK – including mathematicians, computer scientists, geographers, lawyers, physicists, and social scientists, as well as entrepreneurs and government Ministers and Civil Servants. Similar groups have become engaged in other countries, including members of the European Commission. It is not therefore surprising that the terminology used has become highly disparate. The widespread confusion between ‘data’ and ‘information’ is just the most obvious example of terminological imprecision. Conventionally we use a terminology based on a hierarchy of value rising from data to information to evidence to knowledge to wisdom. Data are numbers, text, symbols, etc. that are in some sense value-free e.g. a temperature measurement. Information is formally differentiated from data by implying some degree of selection, organisation and relevance to a particular use, i.e. multiple sets of information may be derived by selections from and analysis of a single data set. In practice, however, the distinction between data and information is often blurred in common usage e.g. ‘Open Data’ and ‘Public Sector Information’ as used in government publications frequently overlap or are used synonymously. In APPSI we have sought to preserve this distinction but we can not avoid sometimes using the terms almost synonymously where we are describing the work of others. That said, APPSI has sought to minimise the terminology problem by creating a glossary made available in wiki form through the good offices of the Cabinet Office ( see http://data.gov.uk/blog/appsi-glossary-terms-open-data-and-public-sector-information) We have tried hard to encourage its wider use and evolution. 1.4 What follows As indicated in the Foreword, the next sections comprise a series of papers and presentations made at the seminar. It begins with the pre-circulated paper to stimulate thinking; each presentation that follows is followed by responses by a discussant and/or rapporteur plus comments made in discussion involving all participants. The final sections are overall summaries. 13 Oxera 2012, Deloitte 2012, McKinsey 2013, ibid 10 The development of Open Data – and the controversies surrounding it and related concepts such as Public Sector Information – continue14. In addition, other big issues have continued to rage over who owns data held by government. This is particularly acute in regard to personal (such as health) data. From such data about individuals can be created valuable Open Data about particular groups of people or relating to geographical areas. But such issues are beyond the focus of this seminar15. 14 On 17 March 2014 the Public Administration Select Committee of the House of Commons published its own report on Statistics and Open Data (http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmpubadm/564/56402.htm). This is commended to readers. It makes a number of important points, some of which echo the discussions in this seminar and previous recommendations to Government by APPSI (such as the disadvantages of including the Postal Address File – a Core Reference Data Set) within the newly privatised commercial body. This report and many other pieces of evidence testify to the significance of Open Data at this time. 15 The common use of the term ‘Open Data’ has excluded data pertaining to human individuals, on the basis that privacy and other factors make this qualitatively different (and sensitive). Yet the potential benefits from use of linked personal data may ultimately be much greater than from ‘conventional’ Open Data’. This would however have to be carried out under a different paradigm involving ‘safe havens’ for the data and stringent governance mechanisms plus convincing citizens that the public benefit would trump risks of disclosure. 11 2. Assessing the real benefits of Open Data: a paper to stimulate discussion at the APPSI seminar on 28 January 2014 Authors: David Rhind and Hugh Neffendorf (with assistance from other APPSI members) Paper This paper was designed to ensure that all seminar participants had at least a basic knowledge of the issues to be discussed and to stimulate the exchange of views in the meeting. It summarised a set of benefits which had been anticipated from Open Data (see Section 1.1) and also the more extensive benefits anticipated by the UK Government in its 2011 consultation paper on Open Data. That paper argued that there are at least six areas where benefits could be obtained. This paper used these as the official benchmarks against which to assess the value obtained. After a brief summary of a number of important previous papers addressing the issue of value obtainable from Open Data, the authors concluded that: Drawing generic conclusions from pre-existing papers was difficult because these focused on different aspects of Open (and related) Data, use different data classifications and terminology, and pertain to different geographies and moments in time. Demonstrating causality and partitioning the elements of success achieved due solely to OD is difficult (see below). Many other factors than the necessary condition of data accessibility determine eventual success – financing, customer interest in the service, marketing, competition, etc. In effect there is a ladder of success factors. Open Data implies minimal tracking of usage with little attention to licensing or registration. As a result, obtaining measures of downloads – let alone better measures of the extent and result of data use – is highly constrained. There is usually a differential distribution of costs and benefits. Rarely do all the costs of Open Data fall where the benefits accrue. In assessing the overall benefits, not only actual incurred costs need to be taken into account: opportunity costs must also be assessed. Whilst some benefits may be accrued rapidly, others take years or even longer to be achieved – complicating the measurement of benefits. There is value in knowing what has not worked. This can guide future actions. The counter-factual needs to be included – what would have happened if OD was not available? Would alternative factors have brought about some of the same benefits? Given all of the above, it is difficult to expect that we can successfully apply just one simple, monetised set of measures of success to the role of Open Data. Different 12 sectors place greater value on some metrics than others, e.g1. profit c.f. the wider public good. Based on studies to date, by far the greatest overall benefits of Open Data and freeing up access to Public Sector Information appear to accrue to consumer surplus. The surplus is manifested at least in part on saving of time, greater convenience and the value to be derived by making more enlightened choices based on good comparative information. Significant levels of social benefit (e.g. environmental quality) are recognised separately in some studies. This may be disturbing for those who see the direct economic benefits of Open Data to be a prime driver for government action. Nevertheless it is a benefit that governments are legitimate to seek. The paper also included some suggestions for enhancing the feedback of levels and type of use. 13 3. Evidence for Benefits of Open Data: the ODUG Case Study Author: Heather Savory, Chair of the Open Data User Group (ODUG) Presentation: 3.1 ODUG. The remit of the Open Data User Group (ODUG) is to: Reach out to Open Data users, re-users, and wider stakeholders; Undertake research and evidence-gathering to inform the business case to release Open Data; Prioritise user requests for data to identify the most important data sets for release as Open Data; Build the business case for the Public Service Transparency Board (PSTB) on how to prioritise funding to deliver Open Data (£7m available in the current Spending Review); Advise PSTB on subsequent spending review bids for additional funding for Open Data to benefit the UK economy. ODUG is also called upon to advise Cabinet Office on Open Data policy and to advise other Sector Transparency Boards. 3.2 The ODUG case studies. The speaker drew out examples from results of a study commissioned by ODUG. Thirty six examples derive from the UK. A further 17 derive from Australia, Canada, Germany, India, Kenya and the USA. Ten Case Studies were described in some detail. All are based on use of simple apps and most are based on exploiting geospatial data. In totality these describe the use of Open Data (whose content varies by jurisdiction) in the public and private sectors; the examples reflect different stages in the evolution of the individual projects. Few give quantified evidence of benefits but most claim productivity or efficiency gains. 3.3 Discussant: Simon Briscoe, Special Adviser (Statistics) to the Public Administration Select Committee and Deputy Chair of UK Data Service. These comments are made in a personal capacity. The considerable efforts of ODUG and those behind Open Data in government are very widely appreciated - and would have been unimaginable five years ago. This should be a cause of national celebration as it will the start of something that will change lives forever. But there are risks: The rhetoric seems to far outstrip the real achievements. This is sadly often the way with matters to do with change in government and with government statistics. Open Data means very different things to different people and while it remains so poorly defined and with the potential outputs so imprecise, it is vital that some very real and 14 identifiable gains are made so as not to disappoint those who are most passionate about Open Data now. Momentum needs to be maintained. The government has yet to accept fully its logical position. Namely that its purpose is to provide public goods - and that open data and statistics are just like a modern equivalent to clean air, better health and roads. In addition, in an era of digital records and transparency, the government has no excuse to fail to publish the anonymised records of its activities in areas such as land registration and much else. Government needs to blow away the vested interest of its civil servants and show that they are public servants on a mission. Open Data is an idea, a spectrum, not something absolute or ‘one off’. If all datasets could be a little more open, then a little more open, over time considerable change would be delivered. The analogy with health is good - lots of little incremental improvements over many years have been transformative in our life expectations. Getting the legal and IT elements of government in shape are vital precursors for Open Data. Gains for the masses and in the way government itself operates must be the main aims -not the vested interests of just the large corporations. To date, as typified by the population census, the reverse has been the main case. All this matters as better and more efficient public policy and more credibility among the voters/public will ensue if better evidence is more widely available. 3.4 Summary of the ensuing discussion by Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven, APPSI: In discussion a number of issues were raised and contentions made: There was a need to provide a clear business model with measureable success criteria, involving verifying and monitoring the success of these apps. The optimum distribution of the investment (from the £7m pot) was difficult to ascertain, particularly because investments would tend to focus on achieving a rapid return. Ensuring Open Data was made available for free was the best way to stimulate small start-ups and innovators. Open Data reduced the complexity of using big data sets, stimulating innovation big or small; Availability to a wider range of enterprises increased business effectiveness and direct and indirect consumer benefit - Google search provided information for free so the consumer benefited directly while Google’s revenue was generated indirectly, resulting in a consumer surplus. Attempts to measure benefit thus far were generally inadequate. Most had tried to quantify and measure it in financial terms while failing to assess the social benefit. The aims of the Cabinet Office in pushing the Open Data agenda were explored by APPSI members. They asked what was the perceived role of Open Data in pushing 15 forward wider public policy and how did Cabinet Office plan to measure the output to determine the level of success attributable to Open Data? 4. The Power of Open Data to Unlock Value Creation Author: Michael Chui, Partner, McKinsey Global Institute Presentation: Michael Chui was the lead author of a report by McKinsey on “Open Data: unlocking innovation and performance with liquid information”: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/business_technology/open_data_unlocking_innovation_and_per formance_with_liquid_information 4.1 Introduction. He stressed that it was too early to assign a properly-quantified value of what had been achieved by the use of Open Data. His report was an attempt to identify the potential rather than the realised value. Michael’s definition of Open Data was wider than that of APPSI and others, including some commercial and other data as well as that made available by governments. He described four characteristics of ‘openness’ of data. Measurement was complicated by the fact that Open Data was often a necessary but not sufficient condition for unlocking benefits and his report had counted all such benefits rather than making a theoretical attribution. He had found that, while the ideal was universal free access to machine-readable data which could be re-used without a licence, substantial benefits could still be realised by, for example, releasing data only to researchers, or data in PDF form rather than machine-readable form. 4.2 Contents and findings of the McKinsey Report. His report had examined benefits in 7 domains – education, transport, consumer products, electricity, oil and gas, healthcare and consumer finance – where an estimated annual total of $3 to $5.4 trillion in economic potential value was available globally. About one-third of the benefits came from benchmarking. In education, for example, instruction could be improved by using data on student performance and learning styles to personalise lessons, yielding between $310 and $370 billion. Much of the benefit was in the form of consumer surplus, for instance by allowing better-informed purchasing or time-saving by citizens. Value could often be enhanced by combining multiple data sets. Governments had a central role to play in realising benefits. They could themselves release data or act as a catalyst to induce others to do so; they could represent shared interests (for instance of consumers); they could use Open Data to improve their own performance; and they could act as regulator. The release of data was not risk-free: individuals and organisations had to beware of the possible disbenefits and, unless carefully managed, the reputation of Open Data could be damaged. 4.3 Summary of the ensuing discussion by Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven, APPSI: In discussion, the following points were made: 16 McKinsey had rightly set Open Data in a broader context by defining the term widely, by underlining the scope to use Open Data in combination with other information, and by stressing that government was not the only source, nor only the source, of Open Data. Geospatial data was particularly important because it was relevant to so many domains. The data must be current if it was to have impact – and the cost and other factors influencing the task of constant updating had to be taken into account in the decision to release it. The release of Open Data was only beneficial if the information was used: awareness-raising, and the availability of apps to interpret Open Data in a way which was accessible to users, were vitally necessary; The UK is currently one of the world leaders in the release of Open Data. 17 5. Ordnance Survey review of OS OpenData costs and benefits Authors: Neil Ackroyd, APPSI member and Deputy Director-General, Ordnance Survey, and John Carpenter, Director of Strategy and Planning, Ordnance Survey Presentation 5.1 Overview. The review commissioned by the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) and Ordnance Survey Assessing the value of OS OpenData to the Economy of Great Britain (https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/207692/bi s-13-950-assessing-value-of-opendata-to-economy-of-great-britain.pdf ) was one of the few detailed studies of benefits based on real data. The number of downloads from Ordnance Survey’s Open Data had been over 300,000 in 2010-11 (its first year) and about 150,000 in each subsequent year. Existing licensees and government bodies (both of whom would have had access to the data previously) accounted for most of the downloads. The use made by social enterprises and SMEs, for whom Open Data was seen by some as the prime market, was an order of magnitude lower. Streetview and vector mapping were the most popular downloads. All this contrasts with the 50,000 downloads in 3 months of the Minecraft game which included Ordnance Survey data. OS had developed an Open Space API to help users customise the data for their specific purposes and had launched ‘Geovation’, a challenge fund to encourage innovative use of Open Data by developers. Serving mobiles is today’s world; serving web sites was yesterday’s world. The reality was that users wanted data in Google formats, not those of the Berners-Lee star ratings. 5.2 Identifiable benefits. Few jobs had been created as a result of the release of Open Data although one user had built a 5-employee enterprise. Ordnance Survey had estimated the increase in GDP consequent on Open Data as £13 to £28m per annum, compared to a cost of £20m. The greatest benefit was internal business efficiencies for users. Extra taxation income was estimated at £2.9 to £6.1m. But these figures took no account of consumer surplus. 5.3 Discussant: Dr Robert Barr, APPSI member. This is an extended version of the discussant’s comments, made in a personal capacity, on the day. 5.3.1 Introduction A breakfast announcement on the 17th November 2009, made by Gordon Brown MP the then Prime Minister, that some Ordnance Survey Data would become available as Open Data took many (including Ordnance Survey) by surprise. This marked a radical change of policy and delighted the followers of the Guardian’s ‘FreeOurData’ campaign. The announcement appeared to radically alter a process that had, since at least the Rayner Review of statistical information initiated in 1979, inexorably created demands from the Treasury that market discipline should be applied to the production, use and charging for information from government agencies. Known originally as the ‘Tradable 18 Information Initiative’ this doctrine lives on in a slightly less extreme form in the Treasury guide ‘Managing Public Money’16. ‘Managing Public Money’ provides clear guidelines on when it is appropriate to charge for information (normally) and whether the charge should be a marginal cost, or at full cost recovery (normal for Trading Funds) (Annex 6.2). It also provides guidelines for the financial objectives of Trading Funds (Annex 7.3). Many hold Ordnance Survey directors responsible for Ordnance Survey’s trading policy. But any discussion of that and the Survey’s Open Data policy should be informed by the demands from the Treasury. Ordnance Survey Is not free to make its own policy outside the Treasury guidelines and negotiations between Ordnance Survey and the Treasury are not open to public scrutiny. The situation is further complicated by the involvement of the Shareholder Executive (ShEx) which acts as de facto 100% owners of the equity in Ordnance Survey on behalf of the government and the public. Specific guidance and instructions to Ordnance Survey from both ShEx and the Treasury are not made public. It would be unfair, in those circumstances, to criticise Ordnance Survey for corporate behaviour which is outside its control. The situation is exacerbated given the role of the Director General and Chief Executive of Ordnance Survey as an, or the, “Adviser on geography to the government” as well as someone responsible for sustaining revenues from government and other sources. This is seen by many outsiders as a conflict of interest, not least since that advice is also not generally made public and many other commercial decisions are deemed confidential. In these circumstances, this presentation provides a welcome degree of insight into where Open Data fits in the Ordnance Survey business model. 5.3.2 The Ordnance Survey Freemium approach Since the Open Data announcement, Ordnance Survey have worked to fulfil the commitment made by the then Prime Minister. This has involved negotiating with an ‘intelligent customer’ to determine which products would be made available, and with the Treasury to obtain funding to recompense Ordnance Survey for the revenue deemed to have been lost from previously traded products which would now be made available free of charge. However the details of how the decision as to which products went into the ‘free’ portfolio and which remained as charged for ‘premium’ products were not made public. This has led to a suspicion that the ‘intelligent customer’ was guided towards those products which had least commercial value for Ordnance Survey, while retaining the most valuable as tradable ‘crown jewels’ to minimise the risk to Ordnance Survey’s commercial revenues. The products which could be considered the ‘crown jewels’ include addresses and their coordinates, building footprints, or the line work that could be used to construct property ownership parcels. These have remained as tradable (i.e. charged for) information. Yet many consider these to be core reference geographies and they are included as priority data sets in the European Union INSPIRE regulations and in Ordnance Survey’s 16 HM Treasury July 2013, Managing Public Money, London. 19 Location Strategy. They have remained securely behind Ordnance Survey’s pay wall for all users who are not part of the PSMA (Public Sector Mapping Agreement). Those excluded include not-for-profit, publicly funded bodies such as Housing Associations, only 20% of which licence Ordnance Survey data. The PSMA is Ordnance Survey’s public sector ‘get out of jail’ card. By negotiating a collective agreement which is paid for by subscription, data has become available to those within the PSMA ‘walled garden’ as though it was Open Data, free at the point of use. The PSMA has been successful in increasing the use of OS data. Another aspect of the ‘Freemium’ model is the provision of data to developers for 12 months which may include a three month ‘royalty holiday’ if products are brought to market during the development licence period. While the take up of developer licences by over 600 organisations is impressive, those that do not develop high value added products which can also bear high OS royalties may well not remain as long term partners. Thus SMEs that do not have the resources, or the potential turnover, to become long term OS partners are unlikely to take advantage of these taster schemes. 5.3.3 Open Data take-up and development programme The efforts made by Ordnance Survey to maximise the take-up of OS Open Data, and to evaluate its contribution to the economy have been impressive, as has the Geovation programme. Nevertheless the attempts at measuring the economic impact suggest that the direct economic activity generated by OS Open Data have been disappointing and has failed to justify the Treasury investment generating only £2.9 - £6.1 million annually of estimated tax revenue against a £20 million expenditure on Open Data. These estimated benefits exclude wider societal benefit, which are difficult to quantify – yet independent studies such as those by McKinsey suggest that most of the benefit of Open Data lies in these areas. There appears to be a pre-occupation that multinational platform providers, already suspected of minimising or avoiding UK taxation through transfer pricing, may be significant beneficiaries of the Open Data provision. An alternative way of looking at this is that these platform providers provide a cost-free and effective mechanism to give UK citizens, and businesses operating in the UK, access to the Open Data from which they gain a benefit from at no cost. There is no direct evidence that the platform provider’s income streams are, or would be, directly enhanced by the availability of the Open Data. Many did not choose to licence the data before it became open, even though the licencing costs would have been small in relation to their revenue streams. This may also suggest that the initial supposition that only relatively low value data sets were released as Open Data - while high value, high utility data sets have been retained as premium paid-for products - may have been right. The test for this is probably not the take up of Open Data, but rather the size of the increase in the use of the premium data by PSMA participants or the increase in use of data by companies in the Olympics project during the period when internal licensing and data sharing restrictions were lifted for Olympic partners. 20 It is difficult to judge Ordnance Survey’s real enthusiasm for the enforced provision of Open Data, particularly if the level of financial support for its release was to decrease. What has been proven by both the Open Data experiment and the PSMA is that, if the aim is to maximise the use of Ordnance Survey’s data (in line with the Association for Geographic Information’s (AGI) mission statement which calls for “the use of Geographic Information to be maximised for the benefit of the citizen, good governance and commerce”), then mechanisms that fund the release of data free at the point of use achieve the aim. 5.3.4 Derived or inferred data It is notable that the final part of the OS Open Data presentation referred to the cause celebre of data deemed to be derived or inferred from OS mapping for which a royalty would normally have been payable as the supposed source mapping was not part of the Open Data portfolio. Arrangements have been made for a significant number of local authorities to be able to release Public Right of Way (PROW) maps, despite the possible misleading nature of such an extract without OS contextual information. Also a wide variety of special and protected area maps have been allowed to be released under derived data exceptions. Yet the list again excludes some of the key ‘crown jewels’. In particular these include property ownership parcels that Her Majesty’s Land Registry and some local authorities are keen to make available. Judging by the popularity and wide use of open cadastral data in countries where it is available, these would be of particular benefit to end users, including the general public. 5.3.5 Conclusion Ordnance Survey are to be congratulated for what they have achieved in increasing the use of their data through bulk buying collective agreements such as the PSMA and through the release, subject to provision of government funding, of a significant quantity of Open Data. Arrangements made to train data users, to sponsor and encourage innovation and to make development use of data possible are also welcome. Yet Ordnance Survey retains a high cost, high value, high margin model for its remaining data. These data – as described above - are often deemed to be the ‘crown jewels. This includes addressing, address locations and much of the large scale topographic data, the detailed transport layer and postcode polygons. Such data are often distributed by value adding re-sellers (who often appear to add modest value but significantly add to price). This market remains contentious, particularly in situations where an effectively captive market, such as that for planning application site and location maps, is being exploited. If those users covered by the Treasury-funded PSMA and those satisfied by the Open Data plus those satisfied by third party map data from open or commercial sources are excluded, Ordnance Survey seems to be attempting to grow a limited or possibly even an ever-shrinking market. Extensive marketing, the management of complex and arcane pricing schemes, the policing of compliance and the pursuit of supposed infringements all add cost, necessitating OS to increase prices and further discourage use. 21 I would suggest that this business model is close to becoming irrevocably broken. An alternative is for Ordnance Survey to become a ‘fee for service’ organisation which maintains a spatial data infrastructure free at the point of use. It is not clear whether this has been fully explored. Such a change would require cooperation from the Treasury and the Shareholder Executive to allow funding to shift from ‘rents’ or ‘tolls’ on data usage to registration charges for activities that cause the map or underlying database to change. Some cadastral systems are already funded in this way, allowing the resulting maintained data to be released as Open Data. Ordnance Survey staff have demonstrated in this presentation that they would be very capable of managing such a regime. What would also be necessary would be for the Treasury and ShEx to accept that Ordnance Survey’s future lies not as a ‘rentier’ business which extracts rent and tolls from the existing database, but one which is rewarded for the underlying task of maintaining our national spatial data infrastructure and maximising its beneficial use. In conclusion, attacks on Ordnance Survey’s apparent unwillingness to convert more of its data to Open Data may have been a case of ‘shooting the messenger’. It is essential that transparent and open policy making extends to our spatial data infrastructure. It is also essential that we find alternative ways of managing our national information framework which maximise beneficial use - rather than maximising the income from a relatively few high value users and excluding many other potential users in the process. 5.4 Summary of the ensuing discussion by Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven, APPSI: In discussion, the following points were made: The OS business model was set by the shareholder – Her Majesty’s Government. That same Government had decided to supply Open OS data free of charge whilst demanding OS also generated substantial revenues from supply of other data (notably Mastermap). The present business model was a complex one which appeared to work to the benefit of Ordnance Survey, but might not be the best one for UK plc as a whole. OS had however demonstrated that the present business model could be adapted to accommodate other cost models when pressing need arose (e.g. for the Olympics). Predictions indicated a massive growth in digital mapping to support non-tradional mapping data uses such as ‘info-minecraft’ and other social enterprise applications. Data was sold increasingly by Ordnance Survey by being embedded in services, moving costs to another point, further challenging the present OS business model. 22 6. The Census as Open Data – costs and benefits Authors: Alistair Calder and Neil Townsend, Office for National Statistics Presentation: 6.1 Background. The Census provided the first major Open Data in the UK. Traditionally, users had had to pay for census data. However following an Invest to Save study in the late 1990s, the data from the 2001 census had generally been made freely available and the policy was continued for 2011 census data. Key factors in the 2011 outcome was the key uses identified – largely Local Government funding and NHS funding allocations plus private sector uses. Not surprisingly, much more use had been made of the data as a result. But it was hard to quantify the change, because user licences (which had previously been counted) were no longer needed, because the number of downloads of census data gave no guide to the intensity with which each dataset was used, and because much of the increase appeared to have been a multiplicity of small uses. 6.2 Costs and benefits. Costs are well known for the past and (relatively) easy to forecast. ONS wished to come to a clear understanding of the benefits of the freelyavailable datasets. This is more difficult and complicated because the costs fall to ONS whilst the benefits accrue to users. An assessment of benefits however was needed to shape future plans (including whether a census based on administrative data augmented by surveys would yield better value). Before each census a business case - with various components in addition to cost – had to be approved by HM Treasury and the plans had to be approved by Parliament. As a consequence ONS had launched a public consultation on the merits of two options for use in 2021 – an up-dated electronicallybased census and data collection based on existing administrative data, much of it personal data about citizens held by Government. ONS had consulted users and user organisations, over 700 of whom had responded. A deliberately-conservative view of the benefits – counted only when the case could be proven - was estimated at £310 million per year and were dominated by commercial cases. Intuitively many of the larger benefits should come again from the public sector applications but it had proved almost impossible to provide robust estimates for them. ONS’s estimate was based on willingness to pay (for instance where local authorities commissioned their own census-type surveys or the amount paid by the commissioners of research which used census data), on the contribution to turnover or investment decisions, or on modelling the welfare loss consequent on the absence of census data or the use of inferior data. The largest identified benefit (£105 million per year) was in retail location planning; £73 million came from market research, £40 million from direct marketing and £33 million from geodemography. Most of the benefit was realised by the private sector – but that might be because private-sector users tended to be more forthcoming about the value of the data and there was probably an unquantified additional value to the research community and local councils and health authorities. 23 6.3 Discussant: Keith Dugmore, APPSI member ONS' presentation does well to start with ‘A little history’. The Census Access project for the 2001 Census can be seen as a major milestone in the history of Open Data. It triggered a great increase in the number of users of Census data, and hence increased the value derived – I’m reminded of Bentham’s contention that “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong”. Having been involved in writing case studies to support ONS’s bid for 2011 Census funding, I’m aware that it is often difficult to express benefits in financial terms, although the use of the 2001 Census by Sainsbury’s to support decision-making when opening hundreds of new stores is one good example. Another emerged unexpectedly when helping the University of Manchester to make the business case for microdata files from the 2011 Census http://www.ccsr.ac.uk/sars/2011/documents/businesscase.pdf Analysis of Census data eventually led to Northern Ireland’s Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister’s announcement of the largest ever US public investment ($150million) in Northern Ireland. Seeking to help the ONS in its subsequent assessment of the benefits of 2011, and also the potential benefits of investing Beyond 2011, it has been possible to arrange discussions with several large commercial end-users of the Census. Again though it has been very difficult to translate usage into quantified financial benefits. Considering the approaches used by ONS, ‘Willingness to pay’ has proven to be unproductive; ‘Valuing research’ is useful; but ‘Estimating the contribution of data to turnover and investment decisions’ has been very helpful. For example, when retailers invest in new stores, the attribution of even a very small percentage of the total costs and benefits as being due to the Census results in very large numbers for the market as a whole. The final approach ‘Welfare loss due to lack of poor data’ would also appear to be a potentially powerful illustration of the value of targeting small areas, and could be illustrated by Lorenz Curves / Gains Charts. In its presentation, ONS pointed out that many such estimates are annually-based, and there is a real risk of confusing these numbers with the cost of a decennial Census. ODUG’s recent case studies are to be applauded. It is striking that these tend to be of use of Open Data by developers / service providers, rather than end-users, and are not focussed on the Census. It is important that demonstrations of the value of Open Data draw on both Census and non-Census, and Developer and End-User examples. Finally, we should not lose sight of the fact that the economists’ cost-benefit analysis does not succeed in measuring all value: By statute, the remit for the UK Statistics Authority and its executive arm (ONS) is for example to produce “statistics for the public good”. 24 6.4 Report of the ensuing discussion by Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven, APPSI: In discussion, ONS was commended for the transparent and energetic way in which they had gone about engaging with a very wide range of stakeholders. There was however a widely-held view that the benefits of the release of census data had been significantly underestimated (for instance, by taking credit for too small a share of the very substantial costs of retail location decisions). Whilst seminar attendees recognised the difficulties involved in estimating benefit amongst public sector bodies, they were clear that these must be much larger than the very conservative figures identified by ONS. Afternote: On 27 March 2014 the UK Statistics Authority published a statement made to Government about the future of the census17. This accepted the National Statistician’s recommendation that the next census in England and Wales should be very much based on collecting the maximum possible amount of data by electronic survey means (an ecensus) and that administrative data should be used to support the census and extend the range of variables when this is safe so to do. The census authorities in Scotland and Northern Ireland published equivalent statements. Underpinning this proposal was a set of several hundred responses to and earlier public consultation on these options. These strongly backed the approach later recommended. Noteworthy in these responses was a comprehensive and strongly supportive one from government departments citing many uses, some previously unknown to ONS, of census data. 17 http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/who-ons-are/programmes-and-projects/beyond-2011/beyond2011-report-on-autumn-2013-consultation--and-recommendations/index.html 25 7. Transparency and Open Data Author: Nick Illsley, Chief Executive, Transport Direct Presentation: 7.1 Key points made. Nick Illsley has played a major role in opening up transportrelated data in the UK, especially real-time data. The main thrust of his presentation is as follows: • Probably the largest demand for performance statistics and access to data is in transport (see slide 7). Public transport (especially rail) is in the spotlight. • Transport data is created and owned by a variety of bodies across the Government, the wider public sector and the private sector and was often most useful when combined with other data such as core geographic and land-use reference data. • There is great variation across sectors (e.g. rail c.f. maritime) in terms of release and also demand • Much Open Data has been released by Transport for London (TfL), Network Rail, Traveline and the Highways Agency • Transparency within the rail industry is essential to facilitate savings and service improvements; transparency outside of rail industry promotes accountability and better information for rail users (Slide 6). • Data are starting to be provided at more granular levels to meet user needs, benchmarking across suppliers is also starting to emerge and users expect that their representatives will tackle poor suppliers. • In TfL opening up data began in 2007 using embedded widgets; by 2013, 5000 developers were using a single API. • The Shakespeare Review estimated that these developments have generated a value of £15 to £58 million each year in saved time for users of TfL. • Conflicts occur at the boundaries of public and private sectors. • Creating new businesses could potentially destroy existing businesses. 7.2 The future. Over the next two years the Department for Transport intends to work with partners and the Open Data community to release a wide range of transport data for use and re-use. The Department will engage with developers and data owners to ensure a broad take-up of the data released and to identify ways in which the data could be made more useful and usable by improving its quality and standardising its formats. This strategy will encompass: • Big Data – the release of core reference datasets that covered definition of transport networks, timetables and traffic figures, planned and unplanned disruption and speed/performance figures. 26 • My Data – the ability for individuals to access information held about them by organisations such as the motoring agencies (and public service operators?). • Satisfaction and Experience Data – the levels of satisfaction from public service users such as the Rail National Passenger Survey and the Bus Passenger Survey as well as extending the powers of the Civil Aviation Authority to encompass passenger experience issues and encouraging the creation of user generated sites similar to Fix My Transport and Fix My Streets; • Creation of Dynamic Information Markets – working with the existing active and creative cadre of developers and service providers that re-use transport data, and with data owners, to create valuable and popular new applications, to grow the market and to increase its value to the economy and to users of the new services provided; • Continuous Improvement of the Quality of Data – reviewing the quality, format and accuracy of transport data, using a number of measures including feedback from developers and end users, provision of meaningful metadata describing the characteristics of the data and its strengths and limitations and the adoption of enhanced formats over time, notably at the point of re-procurement and respecification. 7.3 Discussant: Hugh Neffendorf, APPSI member Nick has shown that transport is clearly one of the main applications and success stories for Open Data, but it is less clear to me that there is quantifiable user benefit. This seems to be a recurring theme. Measurement is confused by confounding issues (like information already being available via various conventional media sources), complex data ownership and lack of agreed definitions. Most usage value is anecdotal from isolated examples. In terms of definitions, I think of Open Data as data made freely available for re-use. So I would discount benefits from organisations using their own data to improve internal efficiency or to inform consumers of their choices, important though these are. Many studies have evaluated mixed concepts. They are not wrong because of that but might give an inflated view of the value of OD. The McKinsey report gives important estimates but takes a very broad view of Open Data, going beyond what I think we would identify with. But among its trillions are probably billions that are genuinely attributable to data re-use. It quotes a few good case studies of value. The Deloitte report for the Shakespeare review was about the value of PSI rather than Open Data, but contains some Open Data insights. In its TfL case study it has a good section on the value of independent Apps that uses assumptions to value their benefits from time savings alone as £15-58m per year. But these assumptions are pretty simplistic. It also mentions the Elgin report that estimates some £25m of benefits. Placr doesn’t include charged-for rail fares data from ATOC that it estimates would add £175m of benefit. The value estimated is considerable but, again, hard to verify. I looked at the travel section of iTunes. This has many independent Apps built on Open Data but it is hard to assess the value from them. iTunes ranks them by most downloaded 27 and ‘top grossing’ but these don’t make for direct measures of value. For instance UK Bus Checker claims over 100,000 downloads at £2 each, which is indicative of appeal but not a measure of benefit. Commercial sensitivity seems to stop disclosure. There are also indirect data issues, like the use of Census data to help with transport planning but the value of these are also hard to measure. I’m aware of extensive use of Open Data in transport planning where it saves money but also contributes to vast amounts of better decisions. How can that be valued? Overall the Open Data value of transport information seems huge but is difficult to estimate with confidence. Do we need to be able to quantify the benefits to encourage further investment and release of data or is it enough to show impressive examples of usage? It is not always possible to quantify concepts that might be intangible, but it should be possible to produce some hard evidence to help build business cases. I’d like to suggest that an independent and focused study should be commissioned to consider the value of Open Data for re-use under a clear definition. 7.4 Summary of the ensuing discussion by Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven APPSI: In discussion, the following points were made: The appetite for information in Transport appeared limitless. Transport data was required, and valued most when combined with location data. Transport had five of the top twenty data sets on data.gov.uk. Evidence supported the massive impact Open Data has had on Transport, together with the high level of innovation and exploitation by SMEs. Open Data did not cover the private sector or outsourced services, supporting an argument that maintenance and provision of important data sets and core reference data should be explicit in the public task of the data custodians. It was uncertain how Open Data would cope with a maturing market. It was also uncertain how the public task would cope with the increasing demands for volume, functionality and quality of Open Data. There was no effective way to value Open Data: while the Deloitte approach had been extensively applied, it was not very scientific and did not address the social benefit context adequately. Transport was time-critical and enabled people to self-organise, establishing a yardstick on which expectations were set. 28 8. Key messages Author: Andrew Stott, Public Sector Transparency Board member 8.1 Overview: the series of presentations had shown that there were clear benefits from making data more widely available. The diversity of examples, and the difficulty of quantifying benefit especially consumer surplus, made it impossible to arrive at a single authoritative figure for the value of Open Data. But it was striking that there was a large and increasing number of examples of beneficial uses of Open Data and an increasing number of neo-millionaires (sadly, not many in the UK as yet) who had developed uses of Open Data which the wider market valued highly. 8.2 Specific points: Michael Chui’s report emphasised the spectrum of benefits which potentially existed. This was a helpful approach. Ordnance Survey and the Office for National Statistics were to be commended for their attempts to measure benefit from Open Data approaches. The evidence to date strongly suggested the greatest benefits were in providing consumer service rather than generating revenue-generating SMEs. Is this likely to continue? Frequency of use by end-users of apps was a useful but not perfect indicator of value. Notwithstanding the commercial and entrepreneurial interests, government remained a very major player. Its contribution is focused on making more data available as Open Data, recognising and supporting the multiple elements of the new information ecosystem (e.g. the ground rules and legislation where necessary and making seed-corn investments). It also needed to ensure that the National information Infrastructure – the core data required for UK to be effectively managed – was as widely available as possible and maintained at an adequate level of quality and currency. There remained an issue about how government should make available Open Data – in as ‘raw’ a form and as early as possible or in more quality-assured and well-documented a form. This should be driven by user views, recognising different views amongst different classes of users. Government had to recognise the reality that major players like Google had created universal platforms with massive resources. Explicit collaboration with such players might be inevitable as well as beneficial. 8.3 Summary of the concluding discussion by Phillip Webb and Duncan Macniven APPSI: Ideally, an assessment of the benefits of Open Data would identify how the world had changed as a result of the availability of data, and measure the results; 29 In practice, measurement of the use and benefits of Open Data was very difficult indeed: the number of downloads of data, for example, really said little or nothing about its utility, and the price people were prepared to pay for an app was an insufficient measure of demand; But it was clear that substantial benefits accrued from the release of Open Data: there was an increasing number of examples of beneficial uses, and clear evidence of the open-market value of information derived from Open Data; Measurement was complicated by the fact that the release of data was a necessary but not a sufficient condition for beneficial use: often an app or other interpretation was necessary for the end-user; While the ideal was universal free access to machine-readable data which could be re-used without a licence (or at least through use of the Open Government Licence), substantial benefits could still be realised by, for example, only releasing data to researchers, or releasing data in PDF rather than machine-readable form; In assessing benefits, it was difficult to generalise because the uses of Open Data were so diverse; Benefits were often in the form of consumer surplus, with small benefits accruing to a large number of people, which further complicated measurement – particularly since consumer surplus was not included in the calculation of GDP; Increased business efficiency was another large source of benefits – but the businesses involved were numerous and diverse and might prefer to avoid publicity; Benefits would tend to increase over time, because most of the costs of releasing Open Data were up-front; The most practical, if time-consuming, approach might be to look separately at each major example of Open Data, identify users, and consult them about the benefits – as the Office for National Statistics had done in relation to census data. 30 APPENDIX 1 Attendees at the seminar Neil Ackroyd Robert Barr Simon Briscoe Beth Brook Alistair Calder John Carpenter Michael Chui Richard Dobbs Keith Dugmore Nick Illsley Marcia Jackson Michael Jennings David Lammey Paul Longley Duncan Macniven Hugh Neffendorf Hilary Newiss Michael Nicholson Bill Oates Shane O'Neill Ed Parkes Ed Parsons David Rhind Heather Savory Andrew Stott Jeni Tennison Geoff Tily Neil Townsend Carol Tullo Phillip Webb Stephen Williams Jim Wretham APPSI member APPSI member Public Administration Select Committee Advisor The National Archives Office of National Statistics Ordnance Survey McKinsey & Co McKinsey & Co APPSI member Dept for Transport The National Archives APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member APPSI member Nesta Google APPSI Chairman Open Data User Group Public Sector Transparency Board Open Data Institute HM Treasury Office for National Statistics The National Archives APPSI member National Audit Office The National Archives 31