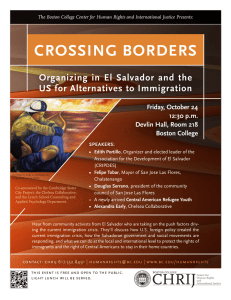

The Center for Global Peace and Conflict Studies

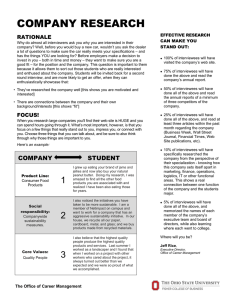

advertisement