The Learning Initiative at the 1991-1994

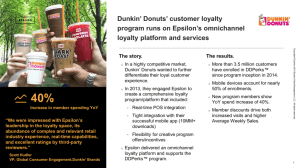

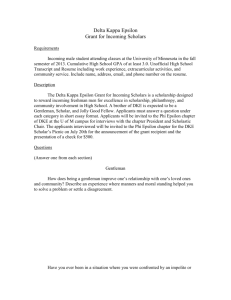

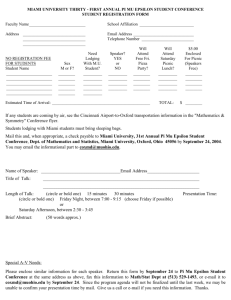

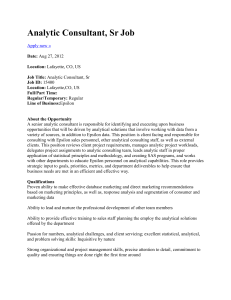

advertisement