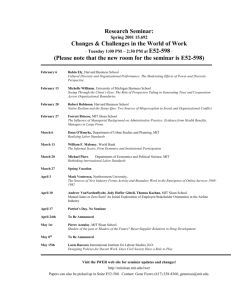

From Theory to Practice October 30, 1995

advertisement